Thermal debinding creates a major bottleneck in the Metal Injection Molding (MIM) process. It takes up to 40% of the total production cycle time. Manufacturers working with tungsten alloys need to master this phase to create high-performance components with complex geometries.

The MIM process gives remarkable benefits for tungsten alloy production and achieves material utilization rates of up to 98%. The technique produces denser, stronger parts than conventional powder methods while creating minimal waste. But thermal debinding comes with its own challenges. Parts can warp or become distorted during heating or cooling if not done right. The process needs precise control because of the 15-20% shrinkage rate during sintering.

Experts with over 20 years in the Metal Injection Molding industry know that thermal debinding and sintering need careful coordination. This is particularly true when working with tungsten – a material prized for its high density and specialized uses in medical, aerospace, and electronic devices. This piece explores thermal debinding theory and compares it with other methods to give practical tips for getting the best results with tungsten alloy MIM components.

Understanding Thermal Debinding in Tungsten Alloy MIM

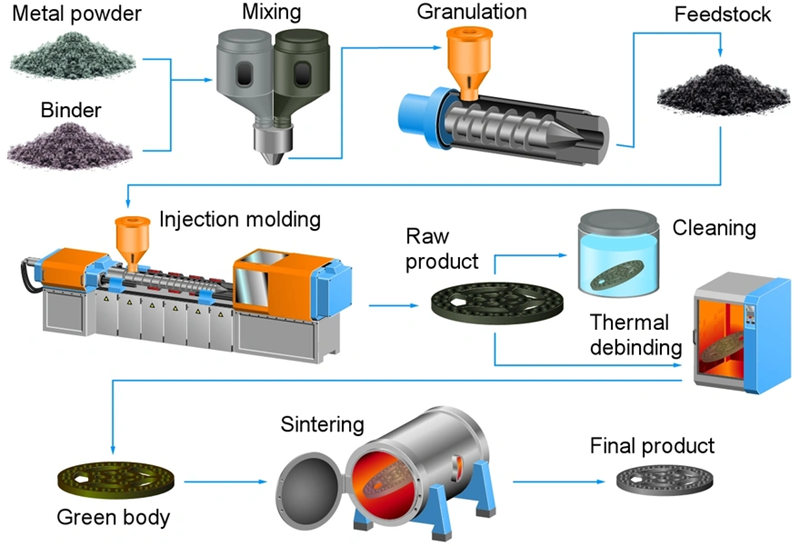

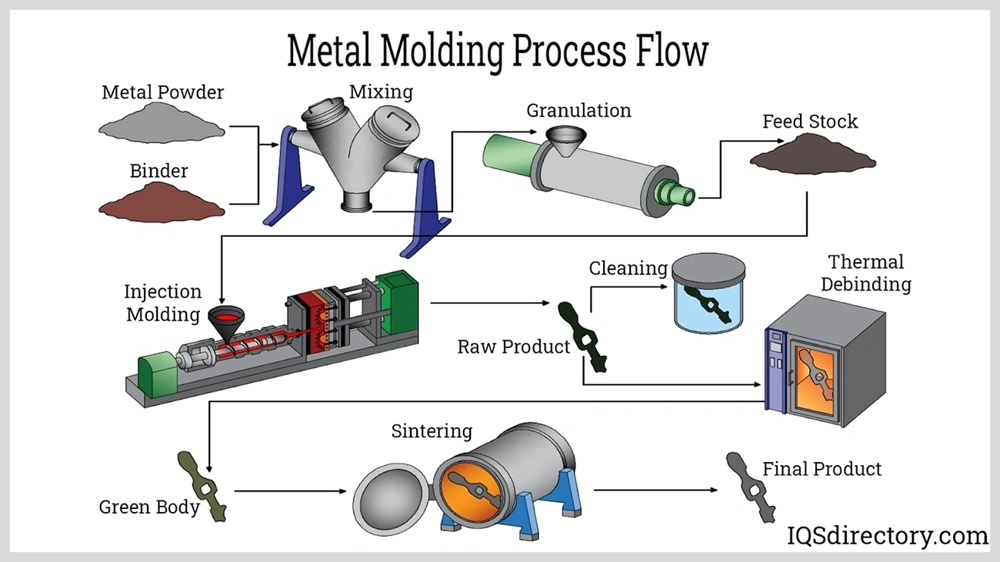

Heat controls the basic mechanism of thermal debinding to remove binder components from metal injection molded parts. This key middle step changes “green” parts into “brown” parts. The parts keep their shape and create a porous network that is needed for sintering later.

Theory of thermal debinding in metal injection molding

Temperature increases based on specific material needs when Metal Injection Molding (MIM) parts go through thermal debinding. The binder starts to soften and melt in its original state. It then breaks down into smaller molecular parts that evaporate through connected pores. The process works mainly through diffusion. Binder components move from inside to the part’s surface before turning into vapor.

You need to control the heating rate with precision to avoid defects. Parts may crack, blister, or change shape if the binder evaporates too fast. So most thermal debinding cycles use slow heating rates. Tungsten alloys typically need a maximum of 2°C/min with planned temperature holds at key points. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) data show that leftover organics must stay under 0.05 wt% to get the best results.

Why tungsten alloys require precise debinding control

Tungsten alloys need exceptional precision during debinding because they react chemically with leftover carbon. Poor debinding causes all but one of these failures to reach 98% density in tungsten components. This happens because carbon left from incomplete binder removal forms tungsten carbide at grain boundaries. These boundaries block proper densification.

When carbon contamination goes above 0.1 wt%, a chemical reaction happens at sintering temperatures: W + C → WC. Tungsten carbide deposits block atomic diffusion paths. They pin grain boundaries and create rigid barriers that resist densification. The density stays limited to 94-96% whatever the sintering time or temperature.

Tungsten alloys need precise atmospheric control during thermal debinding to prevent unwanted chemical reactions. JH MIM’s experience over the last several years shows that laminar flow in the furnace optimizes the process since broken-down binder exists as gas. Tungsten MIM components stay dimensionally stable when debinding cycles follow specific temperature ramp rates and hold times.

Thermal debinding vs solvent and catalytic methods

MIM components can use three main debinding approaches. Each approach has unique benefits and limits:

- Thermal Debinding: Heat alone removes binders through evaporation or breakdown. This method costs less for equipment but usually takes more than 24 hours. Connected pores form slowly compared to other methods.

- Solvent Debinding: Chemicals like hexane, heptane, or trichloroethylene dissolve certain binder parts (usually paraffin and stearic acid). This creates initial porosity and makes thermal debinding work better later. Studies show 316L stainless steel works best with solvent debinding at 60°C for 240 minutes. This method works faster than thermal approaches but raises environmental concerns.

- Catalytic Debinding: Acidic gasses break down binders, especially those with polyacetal. Parts keep their shape well and debind quickly. However, the strong acidic environment limits which metals you can use.

Manufacturers often combine methods, especially for tungsten alloys. A two-stage process starts with solvent debinding that removes 55-65% of total binder. Thermal debinding follows during sintering preheat (300-550°C). This comprehensive approach optimizes efficiency while parts stay dimensionally stable.

Step-by-Step Thermal Debinding Process for Tungsten Alloys

Thermal debinding is the life-blood of tungsten alloy Metal Injection Molding (MIM). You just need meticulous control to create defect-free components. A manufacturer’s excellence starts when they understand how feedstock composition connects with the debinding process.

Feedstock composition and how it affects debinding

The tungsten alloy MIM feedstock has 60% metal powder and 40% binder by volume. Metal powder size ranges from 10 to 25 microns, which ensures proper flow characteristics and sufficient green strength. The binder system’s selection and formulation significantly affect the debinding process. Binders with low viscosity that work well with tungsten powder improve feedstock homogeneity and aid uniform debinding. This reduces defects and distortion risks.

Tungsten alloys need high-quality powder with consistent particle size and shape. This improves feedstock homogeneity and reduces shrinkage variations during sintering. Ultrafine powder fabrication technology also plays a key role in achieving high sintered density and homogeneous microstructures.

Thermal debinding process stages: ramp-up, hold, purge

The thermal debinding process for tungsten alloys follows a carefully coordinated sequence:

- Ramp-up Phase: Temperature rises gradually to prevent defects. Experts suggest maximum heating rates of 1-2°C per minute for tungsten alloys.

- Hold Phase: Strategic temperature plateaus let binder decomposition complete at critical transition points.

- Purge Phase: Continuous gas flow removes decomposed binder vapors to prevent redeposition.

Atmosphere control plays a vital role throughout these stages. Most operations use vacuum or inert gas environments to stop reactive tungsten particles from oxidizing. Gas flow rates should be 25 times greater than the hot zone volume per hour to remove binder vapor effectively.

Binder removal behavior in tungsten-heavy feedstocks

Tungsten-heavy feedstocks show unique binder removal patterns. Primary thermal debinding changes based on the specific feedstock type. Most tungsten MIM feedstocks use polyethylene or polypropylene and wax components. Each component has different melting and vaporization temperatures. A two-stage approach works best.

Lower molecular weight components (usually waxes) come off first at temperatures just above their melting points. Higher molecular weight polymer components then decompose at elevated temperatures. This staged approach creates connected pore networks that help remaining binder components escape.

Thermal debinding process for PVA-based binders

PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) offers a promising, non-toxic, water-soluble binder option for tungsten alloy MIM. PVA’s thermal behavior brings unique challenges. Its thermal decomposition temperature (around 210°C) sits close to its melting point. This makes it prone to dehydration, etherification instead of clean melting.

Manufacturers must modify PVA by adding agents that form hydrogen bonds with its hydroxyl groups to make thermal debinding work. This disrupts molecular regularity, brings down the melting point, and broadens the melting range. A carefully controlled temperature profile then ensures complete binder removal without part defects.

JH MIM has found that combining thermal debinding with preliminary solvent debinding gives the best results for most tungsten alloy components over their 20 years of industry experience.

Key Parameters for Thermal Debinding Success

JH MIM’s 20 years in the metal injection molding industry have revealed four key parameters that determine success in thermal debinding processes for tungsten alloys. The company discovered these vital factors through years of testing and production.

Heating rate and its effect on part integrity

The heating rate is a vital parameter that affects part integrity during thermal debinding. Experts recommend keeping the maximum heating rate at 2°C/min for tungsten alloys. Parts can crack, blister, and distort when this rate is exceeded.

When heating happens too fast, binder components break down quickly. This creates internal pressure that the part cannot handle. The pressure builds up because gas from decomposition cannot escape through the developing pores quickly enough. Modern tungsten MIM operations use temperature sensors right at the parts to maintain precise control throughout the cycle.

Atmosphere control: vacuum vs inert gas

The choice of atmosphere affects part quality and operational efficiency. Two main approaches exist:

- Vacuum debinding removes binder well but has drawbacks. Wax condenses on heating elements and insulation. This wax can crack at higher temperatures and introduce unwanted carbon into the system.

- Inert gas (sweepgas) technology uses argon or nitrogen as carrier gasses to remove evaporated binder components. This method works at higher pressure (10-1 torr not possible). It makes wax collection better and speeds up debinding times.

Positive pressure systems work better than vacuum because they can surround parts in warm gas. This provides more even heating through gas conduction and convection instead of just radiation heating.

Wall thickness limitations and binder migration

The effectiveness of debinding depends on part thickness. Manufacturers limit section thickness to 50mm for tungsten components. Thicker sections make it harder for binder removal because of longer diffusion pathways.

Capillary forces during solvent evaporation can move binder around. This creates uneven distribution throughout the part. Thick sections face this problem more because binder components must travel farther to reach the surface.

Thermal debinding furnace cost considerations

The choice of furnace is a big investment in thermal debinding operations. Three main factors affect the price:

Atmosphere control capability comes first. Air furnaces cost less than inert gas systems. Vacuum furnaces cost the most because they need complex pumps, seals, and special chambers.

Maximum operating temperature makes a huge difference in cost. Tungsten alloy sintering needs furnaces that can reach 1700°C or higher. These furnaces need special heating elements, advanced materials, and sophisticated cooling systems.

Control system complexity is the final factor. Simple controllers just follow temperature profiles. Advanced systems cost more because they include programmable logic controllers, data logging, remote operation, and safety interlocks.

Common Defects and How to Prevent Them

Defects can show up during thermal debinding of tungsten alloy MIM parts even with careful parameter control. Manufacturers have learned about common failures and found affordable solutions through years of hands-on experience.

Cracking due to rapid binder removal

Parts crack when heating rates go beyond the recommended maximum of 0.5-2°C/min. The temperature rises too fast and makes binder components break down quickly. This creates internal pressure that’s too much for the part to handle. The gasses form faster than they can escape through the developing pore networks.

JH MIM suggests using very slow heating rates (0.1 and 0.25°C/min) throughout the thermal cycle to stop cracking. This careful method lets gasses escape slowly and keeps the part’s shape intact. Thick-walled tungsten components need longer thermal debinding hold times to reduce defects.

Surface blistering from trapped gasses

Gasses that get stuck under a part’s outer layer cause surface blistering. This happens in two ways: the outer surface hardens before interior binder can escape, or some binder pockets stay behind after incomplete solvent debinding.

The solution is simple – a longer debinding cycle and better furnace ventilation will eliminate this defect. The right temperature and air flow let decomposition gasses escape from the part easily.

Incomplete debinding and sintering failure

Carbon contamination from leftover binder disrupts tungsten sintering. When residual carbon (0.1-0.5 wt%) meets tungsten at sintering temperatures, it creates tungsten carbide. These carbide precipitates block atomic diffusion paths, stick to grain boundaries, and create barriers that stop proper densification.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) helps spot insufficient debinding. Residual organics should stay below 0.05 wt%. Longer thermal debinding hold times fix the problem when contamination gets too high.

Design tips to reduce thermal stress

Smart design choices help avoid defects during thermal debinding. Here are some proven strategies:

- Keep uniform wall thickness (±20% variation maximum)

- Use minimum 0.4-0.8mm internal radii at corners

- Add flat sintering bases for stability

- Stay away from isolated thick sections over 6mm

These design principles make a big difference in debinding success rates. Parts with less than 1% green density variation reach 97.5-98.5% final density. Parts that go over 2% variation only hit 94-96% density and show visible warpage.

Integrating Thermal Debinding with Sintering

Manufacturing operations become more efficient when thermal debinding and sintering work together as a unified process. This streamlined approach optimizes production and ensures component quality remains high.

Thermal debinding and sintering in a single cycle

A single cycle that combines debinding and sintering brings two key advantages. The overall cycle time drops significantly compared to separate processes. It also eliminates yield losses that typically happen when handling delicate brown parts between individual debinding and sintering steps. Since the 1970s, furnace manufacturers have produced combination debinding-sintering equipment, which was originally designed for tungsten carbide cutting tools.

Setter materials and part positioning

Dimensional stability throughout the thermal cycle depends on proper setters (supporting structures) and strategic part positioning. Graphite retorts are a great way to get uniform gas flow and heating for tungsten alloys. These retorts optimize binder removal while maintaining inert environments. The components need flat sintering bases to remain stable and minimize distortion risks.

Optimizing sintering temperature for tungsten alloys

Temperature sensitivity is a defining characteristic of tungsten alloys. The density stays limited to 96.5-97.5% at 1,455°C due to insufficient liquid phase formation. 1,475°C proves to be the sweet spot, producing 97.5-98.5% density. The density remains at 98% when temperatures exceed 1,495°C, but mechanical properties deteriorate due to excessive grain growth.

The sintering process requires precise hydrogen purity (>99.95%) with oxygen levels below 10 ppm and water vapor at dew points below -60°C. JH MIM’s two decades of industry experience shows that controlled atmosphere cycling determines the final component quality.

Conclusion

Becoming skilled at thermal debinding is crucial to tungsten alloy MIM production success. In this piece, we’ve explored the complex mechanisms behind this vital process – from basic principles of binder removal to practical strategies. Without doubt, the right execution of thermal debinding determines component quality, especially when you have tungsten alloys where precise control stops harmful carbon contamination.

Manufacturers must balance multiple parameters at once. Heating rates, atmosphere selection, part design, and furnace capabilities all work together to achieve the best results. The recommended heating rate of 1-2°C per minute for tungsten alloys prevents defects and will give a complete binder removal. On top of that, proper atmosphere control through vacuum or inert gas systems substantially improves part quality and operational efficiency.

Combining thermal debinding with sintering offers big advantages. This approach reduces cycle time and minimizes yield losses from handling fragile brown parts. The process just needs precise temperature control. This is critical for tungsten alloys where even 20°C variations can dramatically change final density and mechanical properties.

JH MIM utilizes nearly 20 years of metal injection molding expertise to solve these challenges. The company has developed specialized processes for tungsten alloy components. This expertise produces high-density parts with complex geometries consistently, meeting tough requirements in medical, aerospace, and electronic applications.

The success of thermal debinding ended up depending on how well you understand the connection between feedstock composition, process parameters, equipment capabilities, and component design. Companies that excel in these elements can tap into tungsten alloy MIM’s remarkable advantages. They achieve 98% material utilization while creating superior components with exceptional properties.

Key Takeaways

Master these essential thermal debinding principles to achieve superior tungsten alloy MIM components with optimal density and minimal defects.

• Control heating rates precisely: Limit to 1-2°C/min maximum for tungsten alloys to prevent cracking and maintain part integrity throughout debinding.

• Eliminate carbon contamination: Keep residual organics below 0.05 wt% to prevent tungsten carbide formation that blocks densification pathways.

• Optimize atmosphere control: Use inert gas or vacuum systems with proper gas flow (25x hot zone volume/hour) for effective binder vapor removal.

• Design for debinding success: Maintain uniform wall thickness (±20% variation) and avoid thick sections exceeding 6mm to reduce thermal stress.

• Integrate processes strategically: Combine thermal debinding with sintering in single cycles to reduce handling losses and improve overall efficiency.

Proper thermal debinding execution directly determines whether tungsten alloy MIM parts achieve target densities of 97.5-98.5% versus suboptimal 94-96% results. The difference lies in meticulous control of temperature profiles, atmosphere management, and understanding the unique behavior of tungsten-heavy feedstocks during binder removal.

FAQs

Q1. What are the key stages of thermal debinding for tungsten alloy MIM? Thermal debinding for tungsten alloy MIM involves three main stages: ramp-up, hold, and purge. The ramp-up phase gradually increases temperature, the hold phase maintains specific temperatures for complete binder decomposition, and the purge phase uses gas flow to remove decomposed binder vapors.

Q2. Why is precise control crucial in thermal debinding of tungsten alloys? Precise control is essential because tungsten alloys are chemically reactive with residual carbon. Inadequate debinding can lead to carbon contamination, forming tungsten carbide at grain boundaries and preventing proper densification. This can limit the final density of components to 94-96%, regardless of sintering conditions.

Q3. What is the recommended heating rate for thermal debinding of tungsten alloys? Experts recommend a maximum heating rate of 1-2°C per minute for tungsten alloys. Exceeding this rate can cause rapid binder decomposition, leading to internal pressure buildup and potential defects like cracking, blistering, or distortion.

Q4. How does part thickness affect the thermal debinding process? Part thickness directly impacts debinding effectiveness. Most manufacturers limit section thickness to 50mm for tungsten components. Thicker sections extend diffusion pathways for binder removal, potentially leading to incomplete debinding or binder migration issues.

Q5. What are the advantages of integrating thermal debinding with sintering? Integrating thermal debinding with sintering into a single cycle offers two main benefits: it significantly reduces overall cycle time compared to separate processes, and it eliminates yield losses that can occur when handling fragile brown parts between separate debinding and sintering steps.