Warm vertical obturation stands out as one of the best techniques to seal the root canal system during endodontic treatment. Modern endodontics demands a complete seal of the root canal system to ensure treated teeth succeed in the long run. Advanced treatment techniques boost both cleaning and sealing capabilities, which improves clinical outcomes by a lot.

Traditional cold lateral condensation (CLC) struggles to fill oval-shaped canals, lateral canals, and isthmuses effectively. Warm vertical condensation techniques offer better flexibility and sealing potential, especially for complex root canal systems. The warm vertical compaction obturation approach lets practitioners restore the tooth’s natural anatomy. It also ensures complete cleaning of the endodontic system – these factors lead to better long-term prognosis. This explains why warm gutta-percha has become today’s preferred choice for endodontic obturation. The root canal system needs proper cleaning and shaping as basic requirements for warm vertical obturation techniques to succeed.

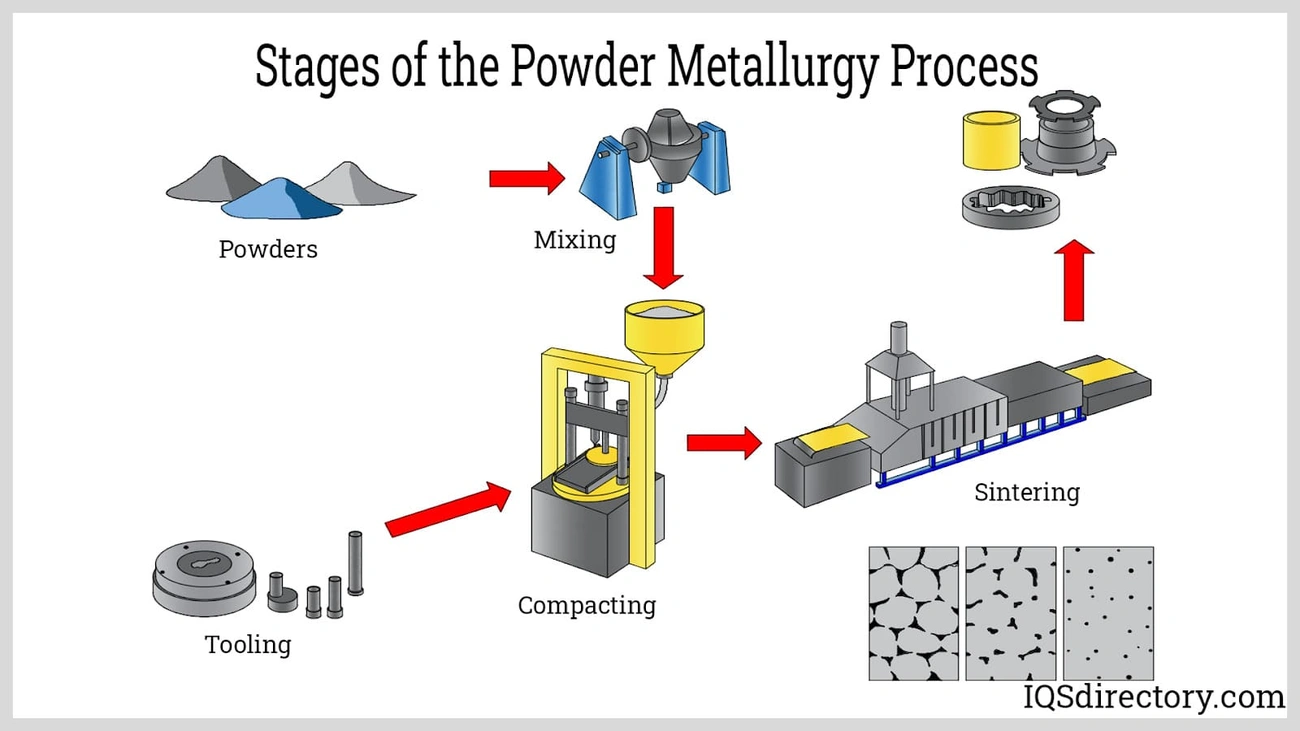

Fundamentals of Warm Compaction in Powder Metallurgy

Powder metallurgy processes use different temperature conditions to get specific material properties. The main difference between conventional methods shows up in their thermal profiles and how materials behave.

Thermal Activation vs Cold Compaction

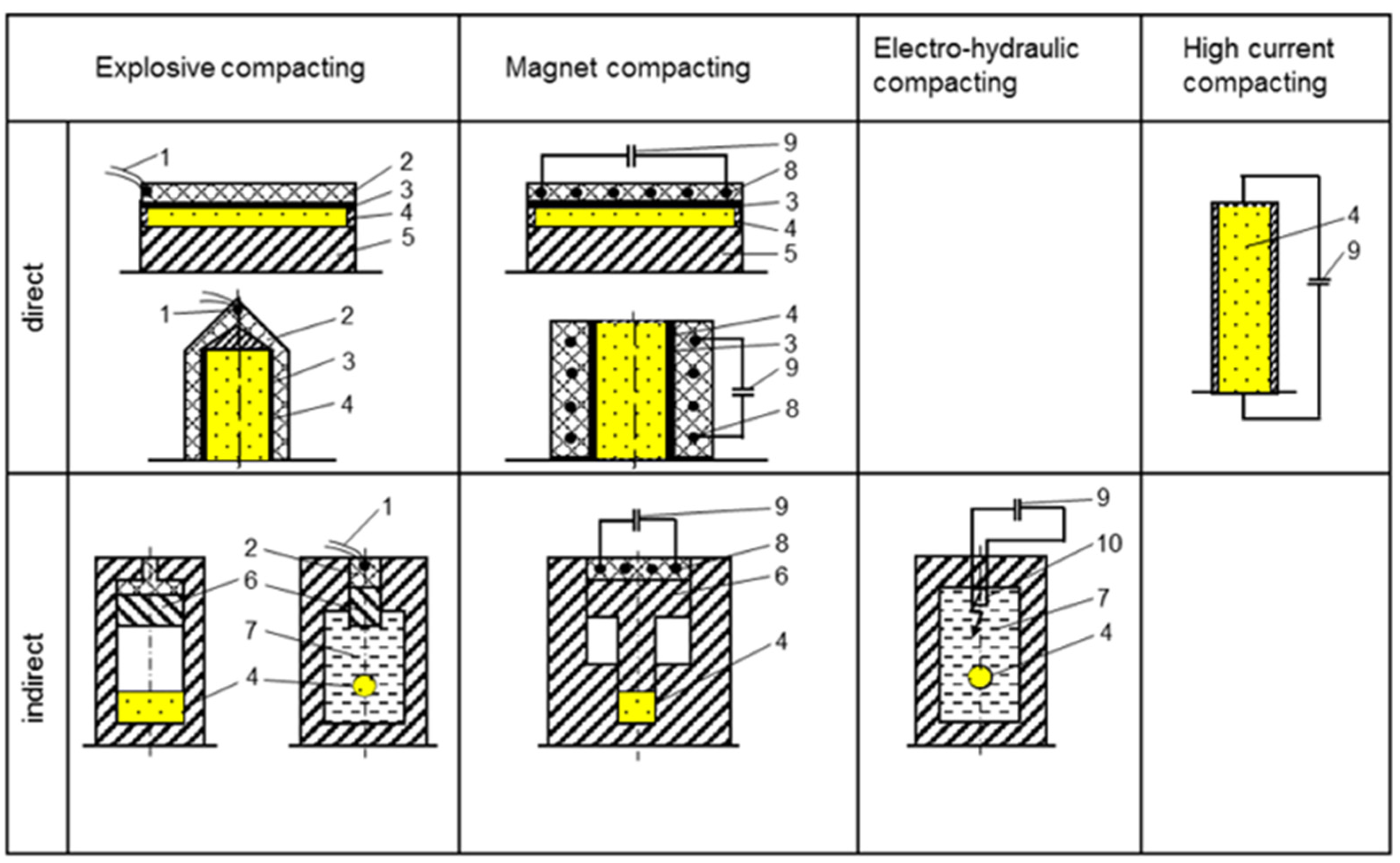

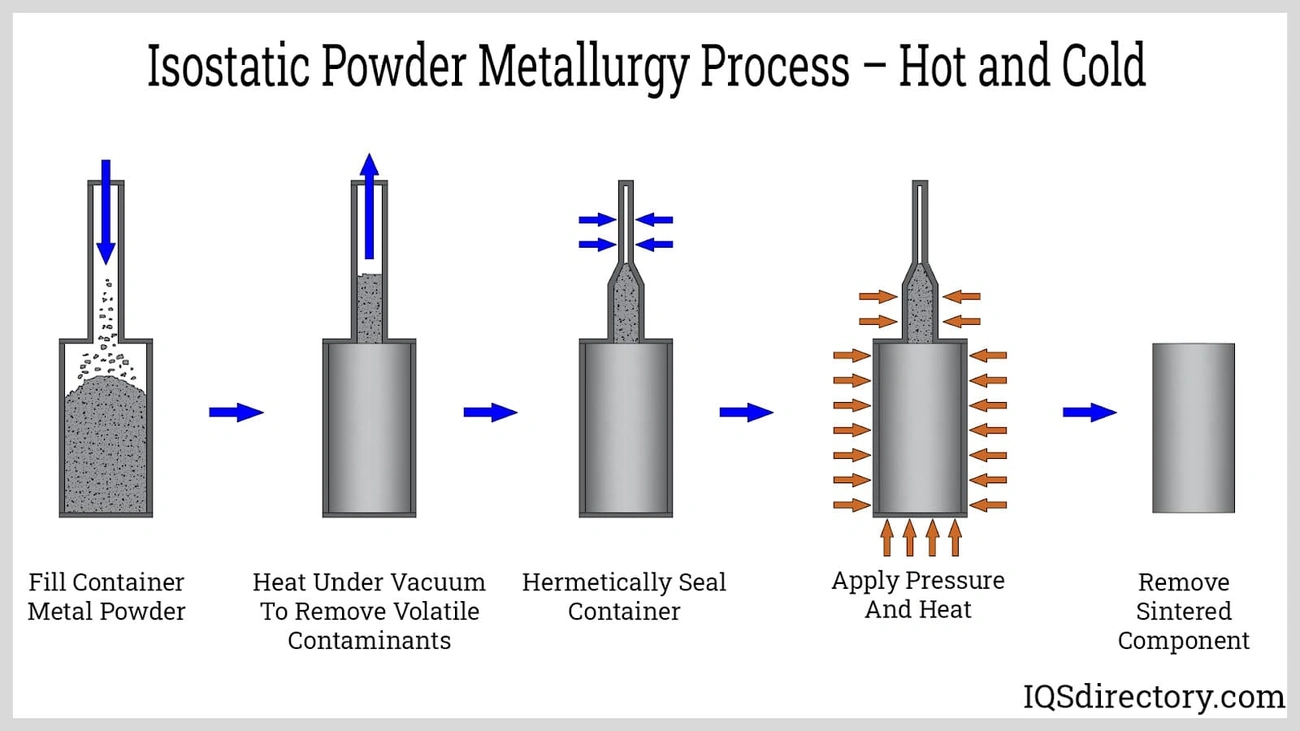

Metal powder mixtures get pressed at room temperature with standard lubricants in cold compaction. Warm die compaction (WDC) heats the die to 90-100°C and needs special lubricants. The process goes further with warm compaction (WC), which heats both the tooling (120-150°C) and the powder (120-130°C) Hot pressing works just below the alloy’s melting point, combining compaction and sintering into one process.

Role of Temperature in Green Density Improvement

Heat added during compaction helps boost component density. WDC lifts density by about 0.13 g/cm³, while full warm compaction achieves a 0.18-0.19 g/cm³ boost. Lower compacting pressures (415-550 MPa) show continuous green density increases as powder temperature rises from room temperature past 150°C, giving density gains around 0.14 g/cm³ over cold compaction. Higher pressures (690-760 MPa) reach peak density at 110°C and stay there until about 125°C before dropping.

Material Behavior Under Elevated Compaction Temperatures

Temperature changes how lubricants work during compaction. Heat makes the lubricant softer, so it moves faster to the die surface and lubricates the tool interface better. Warm processes use advanced lubrication systems that deform more easily than standard lubricants. The link between temperature and die fill matters—green density peaks at 150°C for a 1.0 cm die fill, drops to 110°C for 2.5 cm fills, and reaches 93°C for 3.8 cm fills.

Nano-tungsten powder compacts start showing ductile behavior between 200-300°C. Above these temperatures, green density improves considerably. Each material’s best temperature strikes a balance between two things: getting the most compression while reducing springback during ejection.

Mechanical and Microstructural Objectives of Warm Compaction

Warm compaction stands out as a breakthrough in powder metallurgy. This technique brings better mechanical and microstructural benefits than standard pressing methods. The process hits specific performance targets by controlling temperature conditions and using special lubricant systems.

Targeted Green Strength and Density Uniformity

A well-executed warm compaction process can boost green density by up to 0.15 g/cm³ compared to regular compaction methods. The process also creates better quality pore structures. Green strength values can easily reach 13 MPa (2000 psi), and with special lubricant systems at higher die temperatures, they can go up to 17 MPa (2500 psi) So, parts become strong enough to handle without damage. Under perfect conditions, density can improve by 0.10 g/cm³, though real-world applications usually see gains between 0.05-0.07 g/cm³.

Minimizing Springback and Cracking

Warm compaction reduces green expansion – the energy release that changes dimensions after ejection. Modern lubricant systems cut ejection pressures by 30-50% compared to standard formulas. Metal particle softening leads to this reduction in axial springback, which creates better plastic deformation and stronger particle-to-particle bonds. This results in larger metal-to-metal contact surfaces and better cold welding between particles. The springback along the compaction axis drops as temperature rises, while sideways springback barely changes.

Microstructure Refinement in Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Alloys

Better microstructures from warm compaction lead to stronger mechanical properties in both ferrous and non-ferrous systems. Aluminum alloys show Vickers microhardness values up to 103 HV in fine-grained samples, which beats the usual 60-80 HV range of regular cast versions. Finer microstructures also boost compressive strengths above 500 MPa. Titanium powder systems at warm die temperatures (200°C) can achieve near pore-free results (>99.5% theoretical density) through pressureless sintering. This works great for pure titanium and blended elemental alloys but doesn’t help much with pre-alloyed variants.

Tooling and Process Parameters for Warm Compaction

The success of warm compaction technology depends on how well you control multiple process variables. Each parameter needs fine-tuning to get the best results without affecting component quality.

Die Material Selection for Thermal Stability

Die materials need to handle repeated heating cycles while staying dimensionally stable. Tool steel with better heat conductivity will give a uniform heat spread across the die assembly. The importance of thermal expansion grows as compaction temperatures go up, which directly affects dimensional accuracy.

Lubrication Strategies at Elevated Temperatures

Warm compaction needs special lubricants that work at higher temperatures. The lubricant/binder system should allow smooth powder flow and provide good die wall lubrication to lower ejection forces. Lubricant WP works best between 115-130°C. The lubricant film on die walls stays under 50 Å whatever the lubricant amount (0.5-3 wt%) or compaction pressure (400-800 MPa).

Compaction Pressure Ranges: 400–800 MPa

Pressure levels for warm powder compaction usually range from 400-800 MPa. Powder particles undergo controlled plastic deformation at these pressures and create denser green compacts. Research shows that processes using die wall lubrication should keep pressures above 700 MPa.

Preheating Protocols for Powder and Tooling

Powder delivery systems need heated parts like storage funnels, delivery tubes, and powder boxes that stay at 130°C ±2.5°C. Belt resistance heating works for upper punches, while tube heaters running at about 150°C suit middle dies.

Temperature Control: 100–150°C for Optimal Flow

Best results come from warm compaction between 100-150°C. This temperature sweet spot balances better particle deformation with lubricant performance. Component size affects die temperature – larger parts need lower die temperatures (90-115°C) to avoid overheating during compaction.

Industrial Applications and Performance Outcomes

Manufacturing companies across industries now widely use warm compaction technology. This technology produces components with better density and mechanical properties.

Automotive Gears and Transmission Components

The automotive industry makes use of warm compacted powder metallurgy to create transmission components. Warm compacted synchronizer latch cones for 500 bhp heavy trucks meet tough requirements and cost less than precision forging. These components reach densities of 7.2-7.6 g/cm³ and show 10-40% higher fatigue strength than standard PM parts. Truck transmission planetary gears made through warm compaction have tooth root fatigue endurance limits that surpass solid steel reference gears (33 kN versus 31 kN). Power tools and automotive transmission helical gears also benefit from even density distribution. This allows them to achieve DIN quality class 8 ratings after heat treatment.

High-Strength Structural Parts in Aerospace

Aerospace applications benefit from warm die compaction at 200°C. This process increases titanium powder’s green density by 5.0-9.4% and sintered density by 2.0-4.4% theoretical density. The technique produces near pore-free titanium (>99.5% theoretical density) through pressureless sintering. TiC/316L stainless steel composites made using warm compaction show better mechanical properties and improved corrosion resistance.

Comparison with Cold and Hot Compaction Techniques

Warm compaction costs about 25% more than cold compaction but remains affordable. Cold compacted Astaloy CrL without carbon reaches 7.2 g/cm³ density, while warm techniques achieve 7.5 g/cm³. This results in tensile strength improvement from 257 MPa to 368 MPa.

Integration with Sintering and Secondary Operations

Secondary operations work well with warm compaction. Gear rolling creates pore-free layers deeper than 0.7 mm, which substantially improves rolling contact fatigue resistance. Warm compaction combined with high-temperature sintering achieves densities up to 7.37 g/cm³ at 760 MPa. This combination works especially well when manufacturing gears with custom involute profiles that reduce noise.

Conclusion

Warm compaction technology has proven to be a game-changing advancement in powder metallurgy processes. This 20-year old technique delivers big advantages through thermal activation and improves green density by 0.18-0.19 g/cm³ when compared to conventional cold compaction methods. The improved density leads to better mechanical properties and performance in final components.

Temperature control is the life-blood of successful warm compaction. The best processing range sits between 100-150°C, but engineers need to adjust these settings based on die fill depths and material makeup. Special lubricants designed for high temperatures are vital to achieve better density while they cut ejection forces by 30-50%.

Material properties show substantial improvements through microstructural refinements in warm compaction. Aluminum alloys reach hardness values of 103 HV, compared to just 60-80 HV in cast versions. Parts also show less springback and better green strength, which lets manufacturers create complex shapes with precise tolerances.

Automotive and aerospace industries welcome this technology despite its 25% higher cost than traditional methods. Parts made for transmissions show 10-40% higher fatigue strength than standard powder metallurgy components. The aerospace sector benefits from titanium components that are almost pore-free, with density values that reach beyond 99.5%.

Warm compaction gives manufacturers a powerful way to improve component performance. The technique needs special equipment and careful monitoring, but delivers clear advantages in mechanical properties, dimensional stability, and part quality. These benefits ensure warm compaction’s future as a key manufacturing method for high-performance powder metallurgy applications in many industries.

Key Takeaways

Warm compaction in powder metallurgy offers significant advantages over traditional cold pressing methods, delivering enhanced density, superior mechanical properties, and improved component performance for demanding industrial applications.

• Temperature optimization is critical: Operating between 100-150°C with specialized lubricants increases green density by 0.18-0.19 g/cm³ compared to cold compaction methods.

• Enhanced mechanical properties: Warm compaction achieves 10-40% higher fatigue strength and reduces springback by 30-50% through improved particle bonding.

• Industry-proven applications: Automotive transmission components and aerospace titanium parts demonstrate superior performance, justifying the 25% cost premium over cold compaction.

• Process control requirements: Success depends on precise temperature control, specialized tooling materials, and elevated-temperature lubricants for optimal powder flow.

• Microstructural benefits: The process creates refined grain structures with increased hardness (103 HV vs 60-80 HV in cast equivalents) and near pore-free densities exceeding 99.5%.

Despite higher initial costs, warm compaction technology delivers measurable improvements in component quality, making it essential for high-performance powder metallurgy applications where superior mechanical properties and dimensional accuracy are paramount.

FAQs

Q1. What is warm compaction in powder metallurgy? Warm compaction is a powder metallurgy technique that involves heating both the metal powder and tooling to temperatures between 100-150°C during the compaction process. This method enhances particle deformation and bonding, resulting in higher density and improved mechanical properties compared to traditional cold compaction.

Q2. How does warm compaction compare to other metal forming processes? Warm compaction typically produces parts with better mechanical properties than casting and can approach the strength of forged components. It offers advantages in terms of material efficiency, near-net shape capabilities, and the ability to create complex geometries while maintaining good dimensional accuracy.

Q3. What are the key benefits of using warm compaction? The main benefits include increased green density (by 0.18-0.19 g/cm³ compared to cold compaction), improved green strength, reduced springback, and the ability to achieve more uniform density distribution. These factors contribute to better overall part quality and performance in final applications.

Q4. What types of industries use warm compacted parts? Warm compacted components are widely used in automotive applications, particularly for transmission parts and gears. The aerospace industry also utilizes this technology for producing high-strength structural components. Other sectors benefiting from warm compaction include power tools and various industrial equipment manufacturers.

Q5. Is warm compaction suitable for all metal powders? While warm compaction can be applied to various metal powders, its effectiveness may vary depending on the specific material. It has shown particular success with ferrous alloys, aluminum, and some titanium-based powders. The optimal processing parameters, including temperature and pressure, need to be tailored to the characteristics of each powder system to achieve the best results.