Sintered stainless steel components must have a density of at least 7.2 g/cm³ to work well against corrosion and high temperatures. Manufacturing these components comes with a major challenge – reaching these density values needs temperatures above 2280°F (1250°C). Powder metallurgy relies on the sintering process. The process fuses atoms across particle boundaries to create solid pieces that have less porosity and better physical properties.

Manufacturers now use warm compaction as a proven way to make high-density sintered metal components. The technique boosts the green density of stainless steel powders by more than 0.2 g/cm³ compared to standard methods. These sintered metals are great at removing particles, lasting longer, and standing up to harsh conditions like high temperatures and corrosive environments. Well-made sintered stainless steel mesh and other forms can handle temperatures from 750 to 1750°F based on the alloy material and atmospheric conditions.

This piece looks at the best ways to make high-quality sintered 316L stainless steel and other sintered steel components. It compares different techniques and how they affect the final product’s properties.

Material Selection for Sintered Stainless Steel Components

The right materials are the foundation of making high-performance sintered stainless steel components. Your choice of material will affect how well it compresses, sinters, maintains its dimensions, and the final product’s mechanical strength and resistance to corrosion.

Chemical Composition of 409L and 316L Powders

Stainless steel powders and their chemical makeup affect how they behave during compaction and sintering. 409L and 316L are two different types of stainless steels that have their own unique compositions and properties.

409L is a ferritic, weldable grade with 10.5-11.75% chromium and 0.4-0.8% niobium (columbium). Niobium stabilization stops carbide from getting bigger in heat-affected zones during welding, which keeps the microstructure stable. This grade keeps carbon content at 0.03% max, while manganese and silicon are each capped at 1.0%.

316L is part of the austenitic family and has much more alloy content. You’ll find 16.0-18.0% chromium, 10.0-14.0% nickel, and 2.0-3.0% molybdenum in it. This mix makes it great at fighting off pitting and crevice corrosion in tough environments. The molybdenum helps it resist corrosion better than standard 304 stainless steel. The “L” means low carbon content (max 0.03%), which helps it fight corrosion better and makes it more biocompatible by reducing carbide precipitation.

Particle Size Distribution and Compressibility

The way particles behave shapes both how you can work with them and what your final component will be like. 316L powder usually has particle sizes with D10 values of 17.9-25 μm, D50 values of 30.4-75 μm, and D90 values of 49.8-100 μm. These numbers show the diameter that 10%, 50%, and 90% of particles fall under.

Particle size distribution changes how the sintering process works. Smaller particles give you a better surface finish but might shrink more during sintering. The smaller your median particle size, the higher your final part density will be. In real-world terms, powders with D50 values under 38 μm usually give you higher densities than bigger particles.

Different stainless steel grades compress differently. 409L compresses better than 316L and reaches green densities of 6.00, 6.45, and 6.60 g/cm³ at compaction pressures of 30, 40, and 50 TS. This makes 409L a great choice when you need high density but only moderate corrosion resistance.

316L doesn’t compress as well, but still hits decent green densities of 6.25, 6.60, and 6.83 g/cm³ at those same pressures. It’s harder to compress because it has more alloy content, especially nickel and molybdenum, which make the powder particles harder.

Theoretical Density Considerations

Theoretical density helps us measure how well sintering processes work. Fully dense 316L stainless steel has a theoretical density of 7.98 g/cm³. We use this number as our baseline when calculating relative density percentages.

New compaction techniques are getting us closer to these theoretical values. A high cold pressing pressure of 1.6 GPa boosted the relative green density of 316L samples by 6% compared to regular methods. Sintering at just 1200°C got us to about 97% relative density for 316L.

Green density and final sintered density are linked – higher green densities usually mean higher sintered densities with less shrinkage. This matters a lot when making parts that need to be exactly the right size. That’s why processes like warm compaction, which we’ll talk about later, are great for making precise sintered stainless steel components.

The shape of your particles matters for density, too. Round powders don’t pack as tightly at first but flow better than irregular ones. Loose powder typically hits 40-50% of theoretical density, but tap density reaches 60-65% after you shake it mechanically.

Warm Compaction vs Conventional Compaction: Process Comparison

Manufacturing methods for sintered stainless steel components have moved beyond traditional approaches. Warm compaction techniques now offer better density and strength. Manufacturers need to know the differences between these processes to get the best results for specific applications.

Compaction Pressure: 700 MPa Standardization

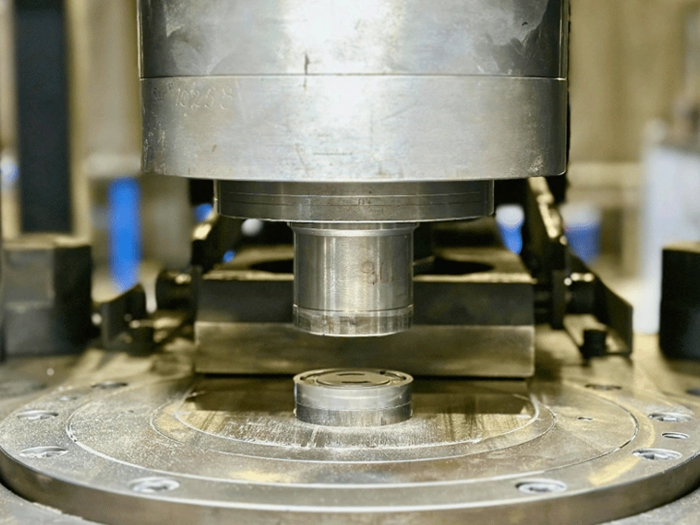

The powder densification and final component properties depend on compaction pressure. The industry uses 700 MPa (51 Tsi) pressure as a standard to get consistent results in sintered stainless steel manufacturing. This standard strikes the right balance between density and tool life.

Softer metals work well with pressures between 200-400 MPa. Harder metals like stainless steel need higher pressures from 400-800 MPa. The pressure settings change based on:

- Material hardness

- Desired final density

- Component geometry complexity

- Expected mechanical properties

Research shows warm compacted specimens at 700 MPa reach much higher densities than conventional methods. This standard pressure also helps compare different stainless steel grades like 409L and 316L under similar processing conditions.

Lubricant Types: Acrawax C vs Warm Compaction Lubricants

Both conventional and warm compaction processes rely heavily on lubrication, but they use different types. Regular compaction uses Acrawax C at about 0.7% to lubricate die walls at room temperature.

Warm compaction needs special lubricants that work well at high temperatures. To cite an instance, see how 409w uses 1.2% specialized warm compaction lubricant while 409c combines 1.0% Amide Wax with 0.2% Lithium-stearate. These special lubricants keep working even when regular ones would melt.

The melting points set these lubricant systems apart. Basic lubricants like stearic acid melt at about 60°C (140°F). Advanced compounds like polyethylene stay solid up to 104°C (220°F). This heat resistance lets warm compaction lubricants:

- Keep even distribution throughout the powder

- Provide steady lubrication at high temperatures

- Stop liquid from pooling on surfaces

- Build better green strength

Green strength results tell an impressive story. Warm compaction lubricants help achieve green strengths over 20 MPa (2900 psi) at various pressures. Special lubricants like FLOMET WP can reach amazing green strength values up to 47 MPa – twice what regular systems deliver.

Tool and Powder Preheating at 100°C

Three main compaction methods differ in their temperature use:

- Cold compaction: The basic method uses room temperature metal powder mix

- Warm die compaction (WDC): Dies heat up to 90-100°C during the process

- Warm compaction (WC): Tools reach 120-150°C while powder hits 120-130°C

Sintered 316L stainless steel production usually heats both powder and tools to 100°C. This temperature makes powder particles more flexible without damaging the lubricant.

Powder heating comes with its challenges because of low thermal conductivity. Good temperature control and even heating systems make all the difference. The extra effort pays off as warm compaction boosts green density by 0.2-0.3 g/cm³ compared to cold methods.

Heat in the compaction process serves one main goal – to increase component density. Higher temperatures help powder particles change shape and arrange better. Better green density leads to stronger mechanical properties after sintering.

Manufacturers can make the best sintered stainless steel components by carefully controlling pressure, choosing the right lubricant, and setting proper preheating levels. This attention to detail ensures the perfect mix of density, strength, and size stability for each application.

Green Properties of 409L and 316L Stainless Steel

Stainless steel powders’ green properties help determine how well components can be handled and their mechanical strength before sintering. These properties help predict the final quality of components and whether they can be manufactured.

Green Density Increase: 0.2–0.3 g/cm³ Gain

Warm compaction techniques offer clear benefits to improve green density values for both 409L and 316L stainless steel powders. Standard compaction pressure of 700 MPa (51 tsi) with conventional methods produces green densities of 6.62 g/cm³ for 316L stainless steel. Warm compacted 316L reaches 6.94 g/cm³ at similar pressure settings. Temperature changes alone create this 0.3 g/cm³ increase.

409L stainless steel shows density improvements with warm compaction, too. The research shows 409L samples gain about 0.2 g/cm³ in green density compared to conventional compaction. We achieved this density improvement through better particle deformation and rearrangement at temperatures around 100°C.

Research on 316L stainless steel confirms that warm compaction produces consistent density gains at different pressure levels. Under 800 MPa pressure conditions, warm compacted 316L shows density values 0.20 g/cm³ higher than cold compaction methods.

Green Strength: 2400+ psi in Warm Compaction

Warm compaction creates much higher green strength values—crucial for handling components and secondary operations. Conventional compaction of 316L with standard lubricants creates green strength measurements of about 9.9 MPa (1436 psi). Warm compaction pushes this value up to 18.2 MPa (2640 psi) for the same material.

409L stainless steel’s green strength rises from baseline values around 9.3 MPa (1350 psi) to more than 16.6 MPa (2408 psi) with warm compaction. This means a 52% increase in green strength compared to conventional methods.

Better green strength comes from several factors:

- Better mechanical interlocking between powder particles

- More even lubricant distribution throughout the compact

- Less elastic springback after compaction

- Better powder consolidation under heat-assisted compression

Effect on Handling and Green Machining

These improvements in green properties change manufacturing capabilities for sintered stainless steel components. Green strength values above 16.6 MPa (2400 psi) make components less fragile, which reduces crack formation during handling and transportation.

Green machining—machining components before sintering—becomes possible as green strength reaches and exceeds 18 MPa (2640 psi). Manufacturers can now perform detailed machining on green components that wouldn’t work with conventional techniques.

Green machining offers big economic benefits. It reduces cutting forces by about 90% compared to machining sintered components. This reduction results in:

- Longer tool life

- Higher production rates (up to 255 mm/min)

- Lower energy consumption

- Reclaimable powdered chips instead of hard-to-recycle sintered chips

Industry standards usually need minimum green strength values around 21 MPa (3000 psi) for green machining operations. Advanced lubricant systems made for warm compaction can reach these levels. Some polymeric lubricants can achieve green strengths up to 48 MPa (7000 psi) after curing.

Warm compaction techniques improve green properties and expand manufacturing capabilities for sintered 316L stainless steel and other grades. This allows complex shapes and better dimensional precision without extra processing steps or special tooling.

Sintering Parameters and Dimensional Change Analysis

Sintering parameters play a key role in determining the quality of sintered stainless steel components. The final product’s quality depends on how well you control temperature, time, and atmosphere during sintering. These factors directly shape the densification, dimensional precision, and performance of components.

Sintering Temperature Range: 1250–1340°C

Temperature is the most important factor that controls dimensional change and final density in stainless steel components. You need temperatures above 2280°F (1250°C) to get high-density sintered stainless steel with the right properties. The industry uses sintering temperatures between 1100°C and 1340°C. The specific range depends on material grade and desired final properties.

17-4PH and 316L stainless steel powders show good sintering compatibility at 1250°C for 60-120 minute. But manufacturers often use temperatures close to 1340°C when they need higher densities. The density improvements are impressive – at 1250°C, relative density hits 94.6%. This jumps to 98.5% at 1300°C and reaches 99.0% at 1350°C.

The sintering atmosphere affects how well materials densify. Components achieve better densification in hydrogen compared to vacuum sintering at the same temperatures. Studies show that shrinkage rates depend on both temperature and atmosphere. Hydrogen creates higher shrinkage rates than vacuum environments, especially at lower sintering temperatures.

Dimensional Change: -3.66% vs -1.84%

Managing dimensional change during sintering is one of the biggest challenges, especially for tight-tolerance applications. At 1280°C, conventionally compacted 409L stainless steel (409c) shows a dimensional change of -3.66%. In comparison, warm compacted 409L (409w) changes less at -3.13% under the same conditions.

316L stainless steel shows even bigger differences. Conventional compaction (316c) at 1340°C leads to a -3.06% dimensional change. Warm compacted 316L (316w) shrinks much less at -1.84% when sintered at 1250°C. This big reduction in dimensional change while keeping target densities gives manufacturers a real advantage.

Sintered components follow standard tolerance grades. Most features in sintered structural parts fall within IT-8/9 tolerances. Some interior dimensions need IT-9/10. Critical dimensions can improve to IT-7 after sizing operations.

Effect of Green Density on Shrinkage

Green density and sintering shrinkage have an inverse relationship. Parts with higher initial density change less during sintering. This explains why warm compaction offers better dimensional stability.

The science behind this is simple. As green density gets closer to theoretical density, there’s less drive for sintering. This means parts with higher green density change less under similar sintering conditions. This relationship is valuable for mass production, where consistent dimensions matter.

Studies with 17-4PH stainless steel show interesting results. Increasing compaction pressure from 800 MPa to 1600 MPa drops volume shrinkage from 12.99% to 3.29% during a 2-hour sintering cycle. This happens because higher relative green density leads to better relative sintered density with less dimensional change.

The density difference between conventionally and warm compacted materials after sintering (about 0.1 g/cm³) is half their green density difference (about 0.2 g/cm³). This shows that sintering activity naturally slows down as parts get closer to theoretical density.

The key to getting the best dimensional stability in sintered stainless steel components lies in balancing three things: sintering temperature, atmosphere, and initial green density. These three factors work together to determine the quality and precision of your final component.

Porosity Distribution and Microstructural Uniformity

The performance of sintered stainless steel components depends on their porosity characteristics. A network of pores exists throughout sintered materials despite efforts to achieve high densification. These pores affect mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and dimensional stability.

Closed vs Interconnected Pores in 316L

Sintered 316L stainless steel has two main types of pores—closed (isolated) and interconnected (surface-connected). Researchers used micro-CT imaging analysis and found that interconnected porosity dominates these structures. Surface-connected pores make up more than 90% of total porosity in samples made from larger particles. This difference is vital because interconnected pores create paths for potential corrosion, while closed porosity adds strength without reducing corrosion resistance.

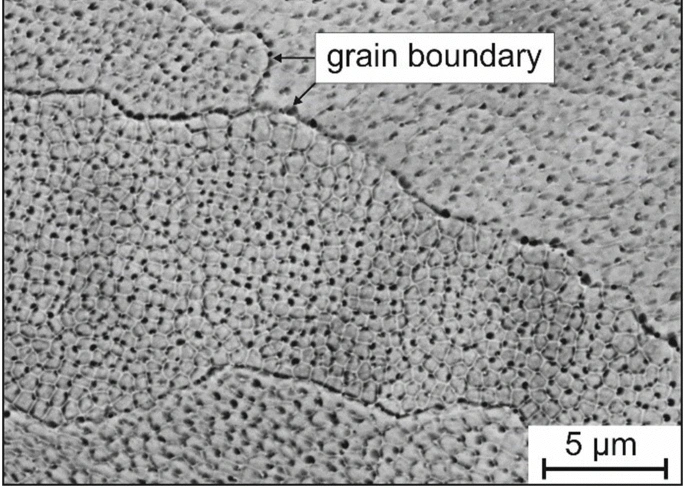

Warm compaction techniques offer better control over porosity distribution than conventional methods. Warm compacted 316L (316w) shows more even porosity distribution compared to conventional compaction (316c). Better particle deformation at higher temperatures leads to this uniformity. Warm compaction removes many large, irregular pores usually found in conventional materials.

Adding phosphorous (Fe₃P) to 316L stainless steel changes interconnected pores into closed ones with rounder shapes. This change happens because phosphorous creates a liquid phase during sintering. The process enhances densification and promotes pore rounding—combining benefits for strength and corrosion resistance.

Metallographic Imaging of Pore Morphology

Pore morphology changes with sintering temperature. Between 1380°C and 1445°C, interconnected pores gradually become isolated and more spherical. Image analysis shows that pores reach their smallest size of 5.3 μm at 1440°C. Raising the temperature to 1445°C can make pores grow to 6.3 μm as they merge.

Clear patterns emerge between porosity percentage and mechanical properties. Higher porosity percentages lead to more irregular pores and reduced mechanical properties in sintered 316L stainless steel. Archimedes’ principle measurements show that sintered samples can reach 79.88%, 82.89%, and 87.71% theoretical density based on processing conditions.

Effect of Lubricant Particle Size on Pore Formation

Lubricant’s characteristics shape the final pore structure in sintered stainless steel components. Larger lubricant particles create bigger pores in the sintered microstructure. These lubricant-induced pores show up in conventional compaction samples (316c) but not in warm compacted (316w) specimens.

Pore size distribution becomes critical for high-performance applications:

- Large, irregular pores act as stress concentration points and limit fatigue resistance

- Smaller, spherical pores have minimal effect on mechanical properties

- Even pore distribution improves dimensional stability and predictability

The largest pores determine fatigue performance more than average porosity, despite competing densification mechanisms. Processes that minimize maximum pore size while maintaining good overall density often give the best mechanical behavior.

Base powder’s particle size distribution controls achievable porosity levels. Research shows that increasing mean particle size from 5 μm to 50 μm can raise porosity from 1.4% to 25%. This relationship helps manufacturers create specific porosity levels for applications like sintered stainless steel mesh filters that just need controlled flow.

Mechanical Properties of Sintered Stainless Steel

Mechanical properties of sintered stainless steel components relate directly to their processing methods and final density. The performance characteristics change substantially based on compaction technique, sintering parameters, and material composition.

Ultimate Tensile Strength: 419 MPa in 316w

Warm compacted 316L stainless steel (316w) shows an impressive ultimate tensile strength of 419 MPa (60.8 ksi). This slightly beats the conventional compacted 316L (316c) which reaches 410 MPa (59.5 ksi). Phosphorus-modified 316L (316p) stands out with superior strength and achieves 549 MPa (79.6 ksi) at similar sintered densities. These strength variations show how composition changes and processing techniques shape the mechanical performance of sintered components.

The sintering atmosphere plays a key role in strength development. Samples sintered in nitrogen show higher strength values than similar compositions processed in argon or vacuum. Tensile strength improves by 5-8% as sintering temperatures rise from 1300°C to 1340°C, depending on the base material’s composition and original green density.

Yield Strength and Elongation Comparison

Yield strength patterns match those of tensile strength across processing variants. Warm compacted 316L reaches a yield strength of 204 MPa (29.6 ksi), which is 19% higher than conventional 316L at 171 MPa (24.8 ksi). Phosphorus additions boost these numbers even more. The 316p reaches 297 MPa (43.1 ksi) – a 74% jump over conventional processing.

The elongation metrics tell a different story. Conventional 316L shows 33.7% elongation, while warm compacted material reaches 28.0% and phosphorus-modified variants hit 28.6%. These numbers suggest that stronger materials might be less ductile, though all values exceed minimum requirements for most applications.

Young’s Modulus and Hardness Metrics

Young’s modulus measurements help us learn about material stiffness. Warm compacted 316L achieves 148 GPa (21.5 Msi), beating conventional material’s 142 GPa (20.6 Msi). Phosphorus-modified 316L gets closer to wrought material values at 162 GPa (23.5 Msi). These numbers stay below the theoretical 200 GPa for fully dense 316L because of residual porosity.

The hardness metrics reveal subtle differences between processing approaches. Conventional 316L measures 91 HV10, warm compacted reaches 94 HV10, and phosphorus-modified hits 142 HV10. Phosphorus-modified materials are a great way to get wear resistance advantages in applications with surface contact or abrasion.

Research confirms that porosity and mechanical performance are directly linked. Both Young’s modulus and peak stress drop as porosity increases. This explains why manufacturing methods that boost densification create better mechanical properties in sintered stainless steel components.

Dimensional Stability and Repeatability in Mass Production

Success in mass-producing sintered stainless steel components depends on dimensional accuracy across thousands of parts. Production runs need both precise dimensions and exceptional repeatability. This approach helps minimize scrap rates and reduces secondary operations.

Ovality Reduction: 22.48 µm to 12.27 µm

Production trials reveal impressive gains in geometric precision with warm compaction techniques. A controlled study with 500 sintered stainless steel rings showed remarkable results. The warm compacted 409L samples (409w) reached an average ovality of 12.27 µm after sintering. This measurement was half of what conventional compacted counterparts (409c) achieved at 22.48 µm. Both samples began with similar green state ovality – 4.78 µm for 409c and 5.78 µm for 409w. The warm compacted components managed to keep better circularity after sintering at 1282°C for 20 minutes in 50%H2/50%N2 atmosphere.

Standard Deviation in Ring Measurements

Warm compaction does more than improve average dimensional values – it boosts manufacturing consistency, which matters in high-volume production. Conventional compaction’s standard deviation in sintered ovality measurements hit 14.69 µm, while warm compaction reached only 9.54 µm. Production-scale mixes that use specialized graphites like CarbQ show a 40% lower standard deviation in dimensional change compared to natural graphite formulations.

Heavy parts in mass production benefit from switching natural graphite with controlled diffusion variants. This change leads to better Critical Process Capability (PpK) – from 1.03 to 1.5. Better dimensional stability means higher manufacturing yield rates and reduced costs.

Implications for Tight Tolerance Applications

Tight dimensional control in production needs systematic optimization throughout the manufacturing chain. This includes everything from powder characteristics to sintering profiles. Sintered structural components typically achieve dimensional tolerances from IT-8/9 for diameters to IT-12 for most other dimensions. The right graphite diffusion characteristics combined with controlled copper distribution make part-to-part consistency better for tight-tolerance applications.

Manufacturers must control these elements daily in mass production:

- Key powder characteristics affecting dimensional change

- Mix formulation and additive grades

- Each manufacturing step in the production process

These advances in dimensional stability now allow sintered stainless steel components to work in demanding applications. Previously, these applications needed expensive machining operations from solid stock.

Phosphorous Additions and Sintering Activation in 316L

Phosphorus additions provide a new way to improve sintered 316L stainless steel properties by modifying microstructure and activating sintering mechanisms.

Fe3P Additions and Closed Porosity Formation

Fe3P phosphide powders make 316L stainless steel’s sintering behavior better by creating a phosphide eutectic liquid phase at around 1050°C. The liquid phase changes how porosity works – it turns interconnected pores into closed ones with better shape. Components with 8-10% phosphide additions reach impressive density values above 96% of theoretical density, and their interconnected porosity drops below 0.2%. Standard 316L without these additions only reaches 80% density, and its interconnected porosity stays high at 17%.

Trade-off: Higher Strength vs Dimensional Change

Phosphorous-modified 316L (316p) shows better mechanical properties, reaching 549 MPa ultimate tensile strength and 297 MPa yield strength. The material’s hardness hits 142 HV10 – much higher than both conventional (91 HV10) and warm compacted variants (94 HV10). These strength improvements come with a major drawback in dimensional stability. 316p changes more during sintering, which can affect how well parts fit together in production.

Comparison with Warm Compaction Results

Performance metrics show that warm compaction strikes the right balance between dimensional stability and mechanical properties. While phosphorous additions create stronger parts than warm compaction, they don’t work well for applications needing tight tolerances. Both methods reach the target density of >7.2 g/cm³, but they do it in completely different ways.

Conclusion

Warm compaction techniques are a better manufacturing method to produce high-quality sintered stainless steel components than conventional approaches. Tests and production data show warm compacted materials have density increases of 0.2-0.3 g/cm³. These materials offer better mechanical properties and dimensional stability.

Manufacturers need to choose carefully between 409L and 316L stainless steel powders based on their specific needs. The material’s characteristics affect compaction behavior differently. 409L works better for compressibility, while 316L gives you better protection against corrosion.

The biggest advantage is how warm compaction cuts down dimensional variability during sintering. Ovality measurements show a 50% improvement over conventional methods. Production runs are more consistent too, with standard deviation measurements showing better results through warm compaction processes.

Adding phosphorus creates impressive strength advantages through liquid phase sintering. The dimensional stability you get from warm compaction makes it perfect for applications that need tight tolerances. You can achieve the best densification by controlling sintering temperatures between 1250-1340°C while keeping dimensional changes predictable.

Manufacturers who want both high performance and dimensional precision should make warm compaction their go-to method for sintered stainless steel components. This technique helps reach the critical density of 7.2 g/cm³ needed for good corrosion and high-temperature properties. It also enables reliable mass production.

Companies like JH MIM, with their 20 years of powder metallurgy expertise, know that warm compaction technology is crucial. It helps deliver precision-engineered products that meet global customer’s demands for performance and precision.

Key Takeaways

Manufacturing high-quality sintered stainless steel components requires strategic process optimization to achieve the critical 7.2 g/cm³ density threshold for superior performance.

• Warm compaction increases green density by 0.2-0.3 g/cm³ compared to conventional methods, enabling better mechanical properties and dimensional control in production.

• Standardized 700 MPa compaction pressure with specialized lubricants at 100°C preheating delivers green strengths exceeding 2400 psi for improved handling capabilities.

• Sintering temperatures between 1250-1340°C optimize densification while warm compacted parts show 50% less dimensional change (-1.84% vs -3.66%).

• Dimensional stability improves dramatically with warm compaction reducing ovality from 22.48 µm to 12.27 µm in mass production scenarios.

• 316L achieves 419 MPa tensile strength through warm compaction while maintaining superior corrosion resistance compared to 409L alternatives.

Warm compaction represents the optimal balance between achieving target density requirements, maintaining tight dimensional tolerances, and delivering consistent mechanical properties essential for demanding stainless steel applications in mass production environments.

FAQs

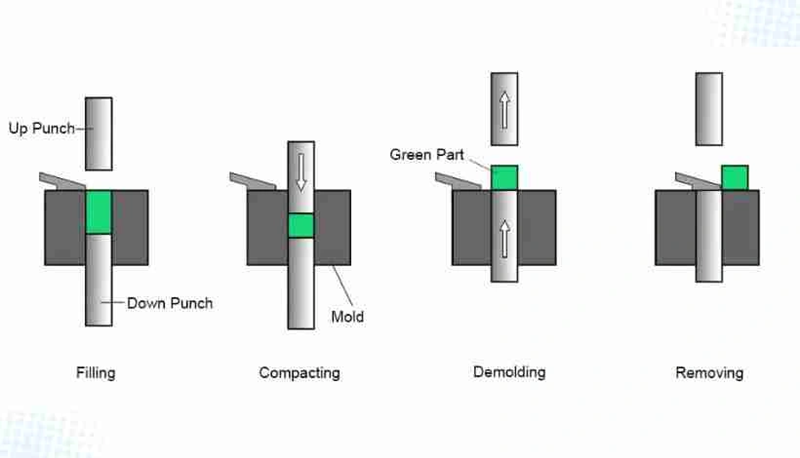

Q1. What are the key steps in manufacturing sintered stainless steel components? The main steps involve mixing metal powders, compacting them in a die under high pressure, and then sintering the compacted part at high temperatures (typically 1250-1340°C) to fuse the particles together. Warm compaction, which involves preheating the powder and tooling to around 100°C, can significantly improve the final properties.

Q2. How does warm compaction improve sintered stainless steel properties? Warm compaction increases green density by 0.2-0.3 g/cm³ compared to conventional methods. This leads to better mechanical properties, improved dimensional stability, and higher green strength (over 2400 psi) for easier handling before sintering. It also reduces dimensional variability in the final sintered parts.

Q3. What density is required for optimal performance of sintered stainless steel? A minimum density of 7.2 g/cm³ is typically required to achieve satisfactory corrosion resistance and high-temperature properties in sintered stainless steel components. Warm compaction techniques help reach this critical density threshold more consistently than conventional methods.

Q4. Can sintered stainless steel parts be machined? Yes, sintered stainless steel parts can be machined, but their porous structure requires special considerations. Green machining (before sintering) is often preferred as it reduces cutting forces by about 90% compared to machining fully sintered parts. This extends tool life and allows for higher production rates.

Q5. How does the choice between 409L and 316L stainless steel affect sintered part properties? 409L offers better compressibility, achieving higher green densities more easily. However, 316L provides superior corrosion resistance, making it preferable for harsh environments. 316L also achieves higher tensile strength (up to 419 MPa) when warm compacted, while maintaining excellent dimensional stability.