Sintered Ceramics

Understanding the Core of Ceramic Sintering

What is Ceramic Sintering

Compacting Solid Materials for Durability

Sintering is a crucial part of the firing process in manufacturing pottery and other ceramic objects. It represents a primary mechanism, alongside vitrification, that contributes to the strength and stability of ceramics. This process begins when ceramic materials reach sufficient temperatures, often between 50% and 80% of their melting point, mobilizing active elements within the material. Once sufficient sintering occurs, the ceramic body becomes resistant to breaking down in water. Additional sintering reduces the porosity of the ceramic material. It also increases the bond area between individual ceramic particles. Ultimately, sintering significantly enhances the overall material strength of the ceramic.

Essential for Ceramic Component Manufacturing

Sintering is indispensable for manufacturing high-performance ceramic components. It transforms loosely packed ceramic powders into dense, robust structures. This process ensures the final product possesses the required mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties for demanding applications. Without effective sintering, ceramic parts would lack the necessary integrity and durability, limiting their use in critical industrial and engineering contexts. The quality of sintered-ceramics directly impacts their performance in various applications.

The Scientific Mechanism of Sintering

Particle Heating and Surface Energy Reduction

The sintering process begins with heating the ceramic powder. As the temperature rises, particles gain energy. This energy allows atoms to move and rearrange, driven by the desire to reduce the material’s total surface energy. Surface energy is high in a powder compact due to the large surface area of individual particles. Reducing this energy is the primary driving force for sintering. In the initial stage, particle bonding initiates as the ceramic powder heats. This leads to surface diffusion and the formation of ‘necks’ between particles, effectively connecting them.

Pore Diminishment and Densification

As sintering progresses, mass transport continues, and densification occurs. Pores begin to shrink as particles further coalesce. This represents the intermediate stage of sintering. In the final stage, pores become closed off, and the structure achieves near-full density. This results in a stronger, more resilient material. Several scientific mechanisms contribute to this pore diminishment and densification:

- Surface Diffusion: Atoms move along particle surfaces, forming necks between particles. This mechanism does not cause shrinkage or densification. It dominates at lower temperatures due to lower activation energy.

- Lattice Diffusion (from surface and grain boundary): Atoms move through the crystal lattice. This leads to true densification as particle centers move closer. This process requires higher temperatures due to greater activation energy.

- Grain Boundary Diffusion: Grain boundaries act as pathways for atomic movement, influencing sintering rates. This mechanism contributes to densification.

- Plastic Deformation: Matter flows through dislocation movement, aiding densification. This occurs especially under applied pressure or high temperatures. It works alongside diffusion processes.

- Pore Elimination: Vacancies diffuse from pores to grain boundaries. This creates elastic stresses and increases sintering rates when grains slide along curved boundaries. Grain boundaries control pore removal, which depends on the ratio of pore size to grain size.

- Thermocapillary Force: This mechanism, identified in advanced processes like laser powder bed fusion, can also contribute to pore removal. It arises from high temperature gradients and pushes pores towards hot regions, facilitating their escape from the melt pool.

The Stages of the Sintering Process

Powder Composing for Optimal Properties

Slurry Creation and Spray Drying

The journey to strong ceramics begins with meticulous powder preparation. Manufacturers often create a ceramic slurry. This involves mixing fine ceramic powders with a liquid, typically water, and various additives. These additives include binders, dispersants, and defoamers. The slurry ensures a homogeneous mixture of particles. After mixing, spray drying is a common technique. It transforms the slurry into free-flowing, spherical granules. This process removes the liquid and creates uniform particles. These granules are ideal for subsequent compaction steps.

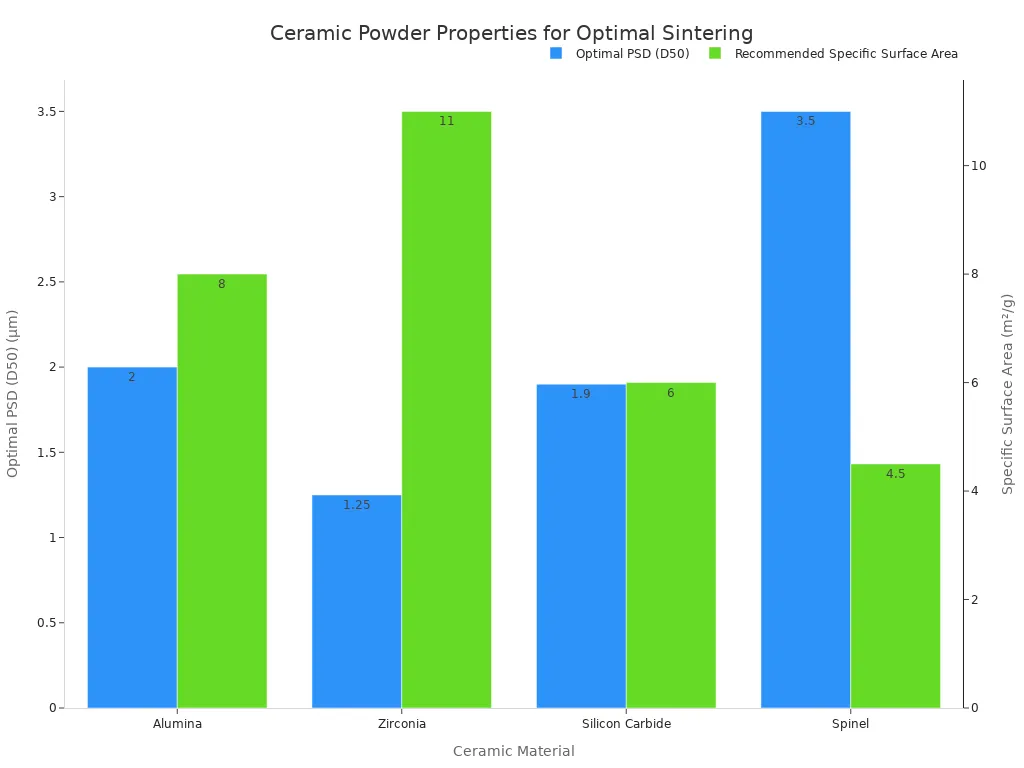

Impact on Final Ceramic Characteristics

The characteristics of the initial ceramic powder significantly influence the final properties of the sintered material. Particle size distribution (PSD) and surface area are critical parameters. They affect packing structure, diffusion mechanisms, and densification rates. A scientifically balanced approach to these parameters allows manufacturers to control microstructure development. It also lowers energy consumption and enhances product consistency. Understanding their interactive roles improves sintering performance. Smaller particles promote higher surface energy. They accelerate neck formation. However, overly fine or overly broad distributions can lead to challenges. These challenges include agglomeration or uneven shrinkage. Reducing the median particle size from 5 μm to 2 μm can lower the sintering onset temperature by 30–50°C. It also increases densification rates. Powders below 1 μm may form stable agglomerates.

| Ceramic Material | Optimal PSD (D50) | Recommended Specific Surface Area |

|---|---|---|

| Alumina | 1–3 μm | 6–10 m²/g |

| Zirconia | 0.5–2 μm | 8–14 m²/g |

| Silicon Carbide | 0.8–3 μm | 4–8 m²/g |

| Spinel | 2–5 μm | 3–6 m²/g |

Optimizing particle size for ceramic applications is crucial. Different ceramic products require unique PSDs. For example, structural ceramics need narrow PSDs for mechanical strength. Functional ceramics often require ultra-fine particles for electronics and energy storage.

- Packing efficiency: Smaller particles fill voids between larger ones. This increases green body density. It minimizes shrinkage and leads to a more uniform final product.

- Sintering dynamics: Fine particles require less energy for full sintering. They fuse at lower temperatures. This improves energy efficiency and ensures consistent densification.

- Surface area: Finer particles offer a larger surface area. This enhances the material’s mechanical and thermal properties.

- Defect reduction: Uniform particle sizes decrease the risk of cracks, voids, and other defects.

- Impact of Particle Size Distribution: Optimizing PSD improves packing density. Bi-modal distributions reduce porosity and enhance product strength. Uniform particles improve material flowability. Controlled PSD ensures efficient sintering. It leads to consistent densification and microstructural uniformity.

Powder Compacting and Green Part Formation

Mechanical Densification Techniques

Compaction of ceramic powders is a forming technique. Granular ceramic materials are made cohesive through mechanical densification. Manufacturers use either hot or cold pressing. This process allows for efficient production of parts with close tolerances and low drying shrinkage. It accommodates a wide range of sizes, shapes, and types of ceramics.

| Parameter | Dry Pressing | Wet Pressing | Isostatic Pressing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure Application | Uniaxial | Uniaxial + Fluid | Hydrostatic (all sides) |

| Tooling | Rigid dies/punches | Similar to dry | Elastomeric molds |

| Shape Complexity | Simple/moderate | Moderate | Complex |

| Uniformity of Compaction | Density gradients | Improved | Highly uniform |

| Automation | High | Moderate | Varies (wet/dry bag) |

These methods offer superior material properties. They produce parts with high density, strength, and hardness. This is especially true with hot pressing techniques. It is crucial for demanding applications.

Creating the “Green Part”

The compacted powder forms a “green part.” This is a fragile, unfired ceramic body. It holds its shape due to the mechanical interlocking of particles and the presence of binders. The green part requires subsequent sintering to achieve its final strength and density.

Achieving Tight Tolerances

Mechanical densification techniques allow tight control over part dimensions. They achieve uniform shapes and sizes with minimal post-processing. This dimensional precision is a significant advantage. It ensures reliable quality. It minimizes variability. This ensures consistent mechanical and physical properties across batches. This is vital for strict quality standards.

| Pressing Method | Pressure Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) | 70–400 MPa | Uniform gas pressure, high densification |

| Hot Pressing | 10–30 MPa | Simultaneous heat and pressure |

| Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) | Up to ~207 MPa | Room temperature, flexible molds |

| Hydrothermal Isostatic Press | ~40 MPa | Lower temperature, specialized applications |

Sintering or Firing for Densification

Kiln Types and Temperature Zones

The sintering process takes place in specialized kilns or furnaces. These kilns are designed to reach and maintain extremely high temperatures. They often feature multiple temperature zones. Each zone serves a specific purpose. For example, a pre-heating zone gradually raises the temperature. A high-temperature zone facilitates densification. A cooling zone slowly brings the material back to room temperature. This controlled heating and cooling prevents thermal shock and cracking.

Atom Diffusion and Particle Fusion

During sintering, atoms diffuse across particle boundaries. This leads to the fusion of individual particles. The driving force for this atomic movement is the reduction of surface energy. As particles fuse, the contact area between them increases. Pores between particles shrink and eventually disappear. This process results in a denser, stronger material.

Pressureless vs. Pressure Sintering

Manufacturers employ two primary sintering approaches: pressureless and pressure-assisted sintering. Each method suits different materials and desired properties.

| Feature | Pressureless Sintering | Pressure-Assisted Sintering |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Sintering process that relies solely on high temperatures to consolidate powder particles without external pressure. | Sintering process that combines high temperatures with external pressure to consolidate powder particles. |

| Mechanism | Material transport occurs through diffusion (surface, grain boundary, volume) driven by surface energy reduction. | Material transport occurs through diffusion and plastic deformation, enhanced by applied pressure. |

| Driving Force | Surface energy minimization. | Surface energy minimization and applied external pressure. |

| Density Achieved | Typically lower densities, often with residual porosity. Full density is difficult to achieve, especially for materials with low self-diffusion coefficients. | Higher densities, often near-theoretical density, due to the enhanced consolidation effect of pressure. Residual porosity is significantly reduced. |

| Processing Temperature | Generally requires higher temperatures to achieve sufficient densification. | Can achieve densification at lower temperatures or shorter times compared to pressureless sintering for the same material. |

| Processing Time | Can be longer to achieve desired densification. | Generally shorter processing times due to the accelerated densification. |

| Equipment Complexity | Simpler equipment (furnaces). | More complex equipment (hot presses, HIP units) capable of applying high pressures at elevated temperatures. |

| Cost | Generally lower equipment and processing costs. | Generally higher equipment and processing costs. |

| Shape Complexity | Can produce complex shapes easily, as there are no constraints from pressure application. | Limited to simpler shapes that can withstand uniform pressure application. Tooling design is critical. |

| Material Limitations | More suitable for materials with high self-diffusion coefficients and good sinterability. Less effective for refractory metals, ceramics with strong covalent bonds, or materials with low diffusion rates. | Highly effective for a wide range of materials, including refractory metals, ceramics, composites, and materials that are difficult to densify by pressureless methods. |

| Mechanical Properties | Generally lower mechanical properties due to residual porosity and potential for excessive grain growth. | Generally superior mechanical properties (strength, hardness, toughness) due to higher density and finer grain structures. |

For example, Si3N4 ceramics begin shrinkage around 1200 °C. Densification with a liquid phase occurs around 1200 °C. Shrinkage increases from 1300 °C. At 1500 °C, shrinkage is -3.2%. These ceramics require a liquid phase (Y2O3, MgO) for densification. Higher temperatures and longer holding times promote large-elongated grains. This enhances fracture toughness and thermal conductivity. However, it can compromise bending strength. Polycrystalline cubic boron nitride (PcBN) shows increased hardness from 44 GPa to 51 GPa between 1200 °C and 1300 °C. This is due to increased densification and intercrystalline bonding. Above 1350 °C, no further hardness increase occurs. Porosity increases due to deviation from stoichiometric equilibrium and nitrogen evaporation.

Role of Separator Sheets in Sintered-Ceramics Production

Separator sheets play a crucial role in the production of sintered-ceramics. These thin, flat materials prevent parts from sticking to kiln furniture or to each other during the high-temperature sintering process. They are typically made from refractory materials. These materials can withstand extreme heat without reacting with the ceramic parts. Separator sheets ensure the integrity of individual components. They facilitate efficient batch processing. This is particularly important for complex shapes or delicate parts.

Factors Influencing Sintered-Ceramics Outcomes

Key Process Variables

Initial Green Compact Porosity

The initial porosity of a green compact significantly impacts the final properties of the ceramic. A lower total porosity and a uniform distribution of fine, rounded pores with low interconnectivity enhance resistance to crack initiation. This also increases compressive strength. Conversely, large, interconnected pores or non-homogeneous microstructures can act as stress concentrators. These reduce Young’s modulus and compressive strength. Adequate densification during sintering requires a sufficiently high green density. However, nanosized particles can achieve sintering from lower green densities compared to coarser particles. Higher green density, achieved through increased compaction pressure, leads to a greater particle coordination number. It also results in a finer, more uniform pore size distribution. This makes pores easier to remove during sintering, leading to denser products. Lower green density can hinder densification.

Sintering Temperature and Duration

Sintering temperature and duration are critical for achieving desired ceramic properties. For zirconia, mechanical properties generally improve as the sintering temperature increases from 1100 °C to 1300 °C. Specifically, 1200 °C is near the peak for densification and optimal for fracture toughness. While flexural strength, elastic modulus, and hardness continue to increase slowly up to 1300 °C, the fracture toughness slightly decreases beyond 1200 °C. Sintering at 1100 °C results in below-normal densification. Higher temperatures can lead to increased grain growth and inter-particle contact, enhancing density and strength. However, a slight decrease in fracture toughness at 1300 °C compared to 1200 °C may be attributed to constantly increasing grain size and decreasing pore size. Residual stress from polymer shrinkage also plays a role. For alumina-reinforced ceramics with a CTN additive, 1050 °C is the optimal temperature for low-temperature sintering. Increasing the sintering temperature beyond this point leads to a decrease in the mechanical properties of the samples. Deviations, such as rapid burnout of the polymer binder, can result in increased porosity, microcracks, and macrocracks. These significantly reduce hardness and flexural strength. The average powder size also plays a crucial role in achieving efficient sintering and desired mechanical properties.

Material Specific Considerations

Pure Oxide Ceramics Requirements

Pure oxide ceramics, such as alumina and zirconia, have specific sintering requirements. Their high melting points and strong atomic bonds often necessitate higher sintering temperatures. They also require precise control over the atmosphere to prevent undesirable chemical reactions. Achieving high density and fine grain structures in these materials is crucial for their performance in demanding applications.

The Impact of Pressure Application

Reducing Sintering Time and Porosity

Applying external pressure during sintering significantly enhances the densification rate. This is considered the simplest way to enhance the densification rate relative to the grain growth rate. External pressure adds to the capillary pressure of pores, thereby boosting densification.

| Effect of External Pressure on Sintering |

|---|

| Impact on Densification Rate |

| Impact on Porosity |

External pressure enhances densification by increasing the sintering driving force. It aids particle rearrangement and promotes diffusion creep. Pressure-assisted processes can minimize grain growth while achieving maximum densification. This allows densification at lower temperatures, which slows the kinetic rate of grain growth. For the applied pressure to significantly influence sintering, it must exceed a threshold pressure. This threshold depends on particle size. This has been experimentally confirmed for nanosized zirconia powder. The application of external pressure during sintering, known as pressure-assisted sintering, significantly enhances the densification rate. It can lead to lower final porosity in ceramic materials. This method is particularly advantageous for high-tech ceramic applications such as transparent ceramics, bioceramics, and structural ceramics. The applied pressure contributes to the sintering driving force and considerably benefits densification of sintered-ceramics.

Benefits and Properties of Sintered-Ceramics

Sintering significantly transforms ceramic materials. It enhances their properties, making them suitable for demanding applications. This process unlocks superior performance characteristics.

Enhanced Material Properties

Reduced Porosity and Increased Density

Sintering effectively reduces porosity and increases the density of ceramic parts. For instance, alumina parts produced through extrusion additive manufacturing, followed by full post-processing, demonstrate less than 1% porosity. This low porosity is crucial for material integrity.

| Condition (Red Clay Ceramic Membranes) | Open Porosity (%) | Density (g/cm³) |

|---|---|---|

| With carbonate (900 °C) | 48.51 | 1.39 |

| Carbonate-free (900 °C) | 41.82 | 1.47 |

| With carbonate (1100 °C) | 39.35 | 1.55 |

| Carbonate-free (1100 °C) | 33.15 | 1.59 |

Vacuum mixing and hot pressing can achieve porosity below 1%. Infiltration plus sintering for 3D-printed ceramics can reduce porosity by over 20%. These methods ensure a dense, robust final product.

Improved Strength and Translucency

Sintering directly influences the strength and translucency of ceramic materials. Altering sintering parameters, such as holding time or temperature, enhances translucency. However, sintering at extremely high temperatures may decrease flexural strength. This occurs due to the migration of yttrium particles to grain boundaries. Variations in the sintering process affect grain size and growth. This impacts both strength and translucency. Enlarged grain size can make zirconia more susceptible to spontaneous phase transformations. This potentially leads to a gradual alteration in strength.

Better Thermal and Electrical Conductivity

The densification achieved through sintering improves both the thermal and electrical conductivity of ceramics. A denser material allows heat and electricity to pass through more efficiently. This makes sintered ceramics valuable in applications requiring effective heat dissipation or electrical insulation.

Preserving Porosity for Specific Functions

Intentional Porosity for Functional Requirements

While sintering often aims for maximum density, manufacturers sometimes intentionally preserve porosity. This creates materials with specific functional requirements. Porous ceramics, made from materials like alumina, silica, and zirconia, retain the strength and heat resistance of conventional ceramics. However, they are significantly lighter due to air-filled pores. These pores also reduce heat capacity and thermal conductivity.

- Zeolite and diatomaceous earth: These are naturally occurring porous materials.

- Honeycomb-shaped porous structures: Manufacturers use these in catalysts.

- Apatite: This material finds use in artificial teeth and bones.

- Porous ceramics for vacuum packing: These hold components and semiconductor wafers during processing. They offer rigidity, high structural stability, and air permeability.

- Porous ceramics for humidity control: Builders employ these as humidity control tiles in construction projects. They repeatedly absorb and release water.

Porous ceramics fulfill requirements such as low density, high specific surface area, and superior thermal insulation. For example, SiC nanowire aerogels exhibit high porosity (94%) and low thermal conductivity (0.046 W/mK). This makes them suitable for thermal insulation. Mullite-reinforced SiC aerogels possess even lower thermal conductivity (0.021 W/mK). Closed-pore porous ceramics are particularly advantageous for thermal insulation. They impede fluid flow and offer high porosity. This makes them applicable in high-temperature insulation across various industries.

Broader Ceramic Manufacturing and Sintered-Ceramics

The Manufacturing Process Overview

The ceramic manufacturing process involves several distinct stages. Each stage contributes to the final product’s quality.

Feedstock Preparation

The process begins with raw material preparation. Manufacturers source, clean, mix, blend, and mill natural clays like kaolin, feldspar, and silica. This achieves the desired composition and uniform particle size. For advanced ceramics, this involves selecting and milling specific powders, such as silicon nitride, to ensure purity and optimal particle size.

Injection Molding

Injection molding is a common forming technique. It shapes ceramic materials into desired forms. This method is particularly effective for producing complex geometries with high precision.

Binder Removal (Debinding)

After forming, a critical step is binder removal, also known as debinding. This process carefully removes organic binders added during feedstock preparation. It prevents defects during the subsequent high-temperature sintering stage.

Finishing Processes for Sintered-Ceramics

After sintering, finishing processes refine the ceramic components. These steps may involve diamond grinding to achieve final dimensions and surface finish. This is necessary due to the extreme hardness of sintered-ceramics. Manufacturers also conduct inspection and quality control. They use non-destructive testing, like ultrasonic or X-ray methods, and dimensional checks. This ensures the product meets all specifications.

Major Ceramic Components and Their Roles

Alumina (Al2O3) in Sintered-Ceramics

Alumina (Al2O3) is a widely used ceramic material. It offers excellent hardness, wear resistance, and electrical insulation properties. Manufacturers use alumina in various applications, including cutting tools, wear plates, and electrical insulators.

Zirconia (ZrO2) in Sintered-Ceramics

Zirconia (ZrO2) is another crucial ceramic material. It exhibits exceptional strength, toughness, and thermal stability. Zirconia’s superior mechanical performance and biocompatibility make it suitable for structural applications, dental implants, and cutting tools. It maintains structural integrity under extreme pressures and corrosive environments. This makes it ideal for medical, industrial, and electronics applications. Zirconia’s extreme hardness and insolubility in water and most acids contribute to its resilience in demanding settings. These include chemical plants and precision tools. Yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) shows high fracture toughness and flexural strength. It also has a high melting point and low thermal conductivity. This makes it beneficial for thermal barrier coatings. YSZ also functions as a solid electrolyte at high temperatures for fuel cells and oxygen sensors.

Sintering represents a fundamental and transformative process in ceramic manufacturing. It directly determines the strength and performance of ceramic materials. Manufacturers carefully control the stages and factors involved, achieving ceramics with tailored properties for diverse and demanding applications. The science behind sintering enables the creation of advanced ceramics. These materials are critical for modern industrial and engineering needs.

(6)

Ceramic sintering transforms ceramic powders into dense, strong materials. It involves heating the powder to high temperatures, causing particles to fuse. This process significantly enhances the material’s mechanical and physical properties.

Sintering is essential because it reduces porosity and increases the density of ceramic components. This process imparts the necessary strength, durability, and performance characteristics for demanding industrial and engineering applications.

The main stages include powder composing, where manufacturers prepare the raw materials; powder compacting, which forms the “green part”; and sintering or firing, where densification occurs through high-temperature treatment.

Sintering temperature and duration are critical. Higher temperatures and longer durations generally increase densification and strength. However, excessive heat can lead to undesirable grain growth or reduced fracture toughness in some materials.

Pressureless sintering relies solely on high temperatures for densification. Pressure-assisted sintering combines high temperatures with external pressure. This accelerates densification, achieves higher densities, and reduces porosity more effectively.

Yes, manufacturers can intentionally preserve porosity in sintered ceramics. This creates materials with specific functional requirements, such as low density, high surface area for catalysts, or superior thermal insulation properties.

Separator sheets prevent ceramic parts from sticking to kiln furniture or each other during high-temperature sintering. They are made from refractory materials and ensure the integrity of individual components, facilitating efficient batch processing.

A “green part” is a fragile, unfired ceramic body formed by compacting ceramic powder. It holds its shape due to mechanical interlocking and binders. This part requires subsequent sintering to achieve its final strength and density.