Archeological discoveries of ceramic artifacts show that sintering practices date back to the upper Paleolithic era, roughly 26,000 years ago. Sintered ceramics remain the lifeblood of modern manufacturing technology. The process works in two ways. It compacts solid materials through pressure and high heat to create a stronger, harder mass by forcing atoms to bond more tightly. The technique works best at temperatures around two-thirds of a material’s melting point, which makes it perfect for materials with very high melting points.

Ceramic sintering creates strong bonds without using glass to hold particles together. The process bonds and packs particles within the ceramic matrix to reduce porosity and boost properties like strength, electrical conductivity, translucency, and thermal conductivity. Pure oxide ceramics need more time and higher temperatures because particle diffusion happens in the solid state. These carefully controlled processes have made sintered ceramic components valuable in many industries. You’ll find them in aerospace, automotive, healthcare, and electronics applications.

Powder Selection and Preprocessing for Sintered Ceramics

Quality sintered ceramics start with the right selection and preprocessing of ceramic powders. Starting materials’ physical and chemical traits shape the final properties of sintered components. Powder engineering lays the groundwork for ceramic manufacturing.

Particle Size Distribution and Surface Area Considerations

Particle size distribution (PSD) shapes how ceramic powders behave during processing and determines the final product’s performance. Manufacturers want fine particle sizes for advanced ceramic applications, usually less than 1 μm in diameter. These small sizes help with sintering and create a fine-grained microstructure in the finished product.

Ceramic powders pack more uniformly when they have narrow particle size distributions. This creates consistent particle contacts throughout the material. Powders with broad distributions show a big drop in surface area with little increase in ultrasonic velocity during early sintering. Different-sized particles create varying thermodynamic forces for sintering.

BET method measures specific surface area, which links directly to sintering behavior. Materials with higher surface area need less activation energy for particle bonding and speed up atomic diffusion. Surface areas above 20-25 m²/g can lead to hard agglomerates that block mass transport during sintering. Finding the sweet spot between particle size and surface area needs careful balance.

Binder and Additive Selection for Green Body Formation

Binders make ceramic processing possible by strengthening green bodies—unfired ceramic shapes that hold their form before sintering. Good ceramic binders need minimal ash after firing, quick burnout at low temperatures, better mechanical strength, and they must work well with other processing steps.

Ceramic binders come in two types:

- Inorganic binders (sodium silicate, bentonite, magnesium aluminum silicates): These cost less and resist microbiological attacks. Black coring issues never happen during firing with these binders. Adding 0.5-3.0% bentonite, a natural montmorillonite material, makes green strength better.

- Organic binders (polyvinyl alcohol, starches, carboxymethylcellulose): These create hydrogen bonds between particles as they dry, building a stronger three-dimensional structure. Adding more organic binders can boost drying strength by up to 30%.

Deflocculants or dispersants like fatty acids and esters keep ceramic particles stable in suspension. This helps achieve high particle loadings and quality ceramic parts. Plasticizers make tape casting or extrusion methods easier by improving flexibility.

Spray Drying and Granulation Techniques

Making fine ceramic powders into flowable granules helps with many forming operations. Spray drying leads the way in producing granulate for green body formation. The process works in three steps: atomization creates droplets, solvent evaporation turns droplets into particles, and then particles get collected.

Atomizing gas rate in spray drying affects droplet size and dried granule size. This method turns ceramic slurry into dry, granular powder that flows better, packs denser, and compacts stronger. These round granules usually measure between 100-300 microns—perfect for pressing operations.

Well-controlled granulation creates particles strong enough for handling but designed to break down evenly under pressing forces. This prevents defects in the final sintered product. The process also cuts down dust during manufacturing, which makes work safer and more efficient.

Good sintering needs carefully engineered granule shapes. This depends on controlling slurry concentration, original particle size, and equipment setup.

Compaction Techniques for Green Body Formation

Making ceramic powders into a stable green body is a vital intermediate step in ceramic manufacturing. The chosen compaction method shapes the microstructural uniformity and final performance of sintered ceramic components.

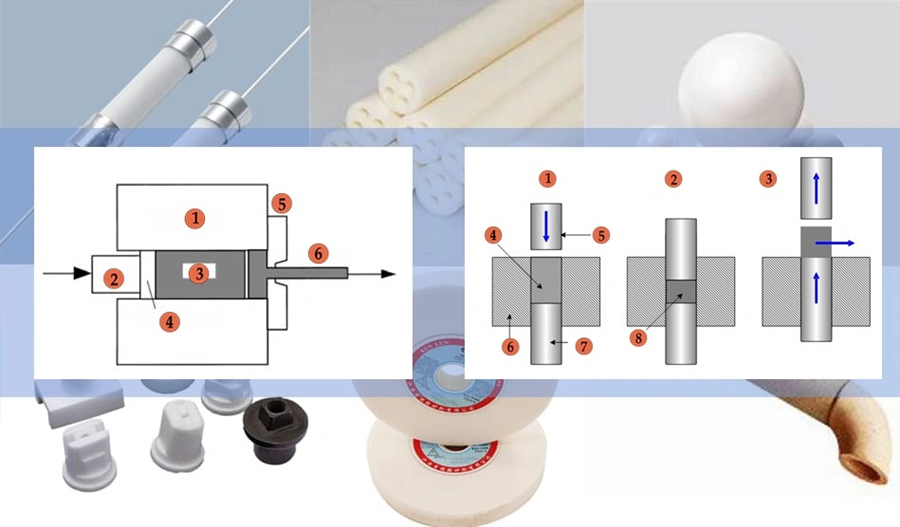

Cold Isostatic Pressing vs Uniaxial Pressing

These compaction techniques differ mainly in how they apply pressure to ceramic powders. Uniaxial pressing uses top and bottom punches to compress powder along a single axis within a rigid die cavity. Cold isostatic pressing (CIP) uses a fluid medium to apply uniform pressure from all directions.

The uniaxial pressing cycle creates green bodies through three distinct stages. Particles rearrange below 0.5 MPa, then granules deform and fracture to eliminate intergranular porosity. The final densification happens at pressures above 250 MPa. This technique has its drawbacks due to the wall friction, which creates density gradients. Materials become less dense as they get further from the punches.

CIP solves these problems by using flexible, elastomeric molds submerged in fluid within high-pressure chambers. The method almost eliminates density variations from friction. It operates at pressures between 100-400 MPa to achieve even consolidation. The benefits are clear:

- Components have more consistent density throughout

- Complex geometries with undercuts and long aspect ratios are possible

- Shrinkage during sintering becomes more predictable and even

- Green strength increases, making handling easier before firing

Uniaxial pressing works best for mass production of simple forms because it offers high dimensional precision and quick production cycles. Standard processes typically achieve relative green density between 50% and 65%.

Injection Molding Feedstock Preparation

Ceramic injection molding (CIM) lets manufacturers create complex three-dimensional parts with tight dimensional tolerances without expensive post-processing. Success depends on well-prepared feedstock—a uniform mixture of ceramic powder and thermoplastic binder.

The preparation starts by mixing ceramic powders with polymer-based binders at high temperatures. Manufacturers add powder gradually to the molten polymer mixture. They use agitators or extruders to ensure high shear rates and uniformity. The best feedstocks need solids with a thin binder coating without component buildup.

Powder usually makes up about 50% of the mixture’s volume. This balance helps maintain injection capacity and sufficient cohesion during debinding. Binder systems combine thermoplastics (polyethylene, polypropylene), waxes for lower viscosity, and surfactant agents that help mixing. The material cools down and becomes granules ready for injection.

Theory suggests feedstocks with high solid loadings are better because they provide high green densities. The catch is that increased viscosity limits how well the material flows. The best feedstock finds the sweet spot between solid loading and minimum binder content.

Green Density and Shape Retention Metrics

Quality control relies heavily on measuring green body density before sintering. Scientists use several methods: mass-volume measurement, powder compacted pycnometry, and mercury porosimetry.

Research comparing these methods revealed interesting results. Powder compacted pycnometry gives repeatable results to the second decimal place. Mass-volume techniques depend more on who performs them. Non-contact ultrasound velocity measurements correlate well with bulk density measurements. They showed correlation coefficients (R²) of 0.88 for cylindrical and disk samples made from similar alumina powder.

Pressed alumina cylinders show predictable green body densities at different pressures. At 142, 85.0, 56.6, and 35.4 MPa, densities measure approximately 2.22, 2.15, 2.10, and 2.04 g/cm³ respectively. This pattern shows how compressibility directly affects achievable green density at specific compaction pressures.

Shape retention during processing is another vital metric. Material and process factors substantially influence shape retention, which affects surface quality and ceramic part strength during binder removal. The best results come from feedstocks that balance good moldability with enough resistance to deformation during thermal debinding. Careful control of these parameters helps manufacturers consistently make ceramic components with better mechanical properties.

Thermal Sintering Methods and Kiln Design

The final properties of sintered ceramics depend on proper kiln design and thermal processing. Specialized equipment transforms delicate green bodies into strong, dense components through controlled heat application. These components have specific physical and mechanical characteristics.

Tunnel Kiln vs Periodic Kiln Temperature Profiles

Ceramic manufacturers mainly use two types of kilns with unique operational features. Tunnel kilns never cool down completely and operate continuously as ceramic parts move through on cars or conveyor systems. Periodic kilns work in cycles that include loading, heating, cooling, and unloading.

Large-scale ceramic production benefits from tunnel kilns. They provide temperature control accuracy within ±5°C and distribute heat evenly throughout the kiln chamber. These features ensure products maintain consistent quality and appearance. The downside is that tunnel kilns need a large upfront investment and can be affected by weather events.

Manufacturers prefer periodic kilns for their flexibility. They can adjust firing schedules based on different product types. The working conditions are better too, since loading and unloading happen outside the hot kiln. This setup leads to faster turnaround times.

Temperature profiles work differently in these kiln types. Periodic kilns expose all materials to temperature changes at the same time. Tunnel kilns create a temperature gradient in space, with each section staying at specific temperatures.

Preheat, Sintering, and Cooling Zone Functions

Both kiln types have three temperature zones that work in different ways. The preheat zone slowly increases temperature to remove moisture, lubricants, and organic materials from green bodies. This slow warming prevents damage to ceramic components from thermal shock.

The sintering zone reaches the highest temperature where powder particles fuse through atomic diffusion. Temperatures in this zone typically range from 1000°C to 2000°C, based on material needs. Piezoelectric ceramics sintered in tunnel kilns show a complex relationship between process settings and final product quality.

Temperature reduction happens gradually in the cooling zone to prevent thermal shock, cracking, and oxidation. The cooling process needs careful control. Uneven cooling can create temperature differences within ceramic components, leading to phase, compositional, or microstructural variations.

New research shows that placing samples vertically inside the furnace and using highly conductive supporting plates reduces temperature differences between top and bottom surfaces. Maximizing exposure to radiative heat transfer plays a key role in successful sintering.

Pressureless Sintering for Metal-Ceramic Composites

Metal-ceramic composites can be made through pressureless sintering, which uses heat without external pressure. This method works great for functionally graded materials (FGMs) where composition changes gradually across the component.

Pressureless sintering might not achieve full densification like pressure-assisted methods, but it can produce complex shapes that wouldn’t survive uniform pressure. Here’s how pressureless and pressure-assisted sintering compare:

| Feature | Pressureless Sintering | Pressure-Assisted Sintering |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Material transport through diffusion driven by surface energy reduction | Material transport through diffusion and plastic deformation, enhanced by pressure |

| Density Achieved | Lower densities with residual porosity | Higher densities, often near-theoretical density |

| Processing Temperature | Higher temperatures required | Lower temperatures possible |

| Equipment Complexity | Simpler equipment (furnaces) | More complex equipment (hot presses) |

| Shape Complexity | Complex shapes possible | Limited to simpler shapes |

Initial and final porosities affect how metal-ceramic composites sinter, especially when particles clump together. Engineers use this knowledge to design components with optimal gradient structures.

Advanced Sintering Techniques for High-Performance Ceramics

Advanced sintering techniques have emerged as alternatives to conventional thermal methods. These new approaches tackle the limitations of processing time, energy use, and material properties in sintered ceramics. They open up possibilities that traditional sintering could never achieve.

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) for Full Densification

HIP technology uses uniform gas pressure on ceramic materials while exposing them to high temperatures. The process applies hydrostatic pressure up to 400 MPa through inert gas (typically argon) at temperatures reaching 2000°C. This combination creates better densification without the density variations you see in uniaxial pressing.

The technology produces ceramics with consistent mechanical properties by reducing porosity to less than 0.001%. Components need minimal post-processing because the omnidirectional pressure creates near-net shapes. HIP’s pressure range is ten times higher than conventional hot pressing, which makes it perfect for creating fully dense ceramic components.

Many manufacturers get the best results with a two-stage Sinter-HIP process. They first sinter the ceramic to closed porosity (92-96% density) and then apply HIP treatment. This method creates fully dense composites and keeps grain growth lower than traditional approaches.

Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) for Nanostructured Ceramics

SPS, also known as pulsed electric current sintering (PECS), is a game-changer for making nanostructured ceramics. The process sends pulsed direct current through both the die and ceramic powder while applying uniaxial pressure up to 0.15 GPa.

SPS stands out because of its incredible heating rates—up to 1000°C/min. These rates come from Joule heating as current flows through the powder. The quick heating and moderate pressure help achieve full density at temperatures 200-500°C lower than regular sintering. This preserves nanoscale features that would normally disappear during long exposure to high temperatures.

The technique works great for making bulk nanostructured ceramics where controlling grain growth is crucial. Scientists have created ceramic materials with grain sizes as small as 90-250 nm by carefully controlling processing parameters. These materials have better mechanical properties than those made through conventional sintering.

Microwave and Flash Sintering for Rapid Processing

New rapid ceramic processing methods have cut sintering time dramatically. Flash sintering can process ceramics in under 10 seconds—much faster than conventional methods that take 1,000 times longer. The process uses an electric field on ceramic powders that causes a sudden current increase, leading to almost instant densification.

Microwave sintering heats materials differently. It uses electromagnetic energy that goes straight into the material’s core. This creates even heating throughout instead of relying on heat moving in from the outside. Some ceramics achieve 80-90% heating efficiency this way, using 90% less energy than conventional sintering.

Both methods speed up densification and minimize grain growth, which creates finer microstructures with improved properties. These techniques work particularly well for dense nanostructured ceramics, advanced metal-ceramic composites, and complex shapes that regular methods can’t handle effectively.

Microstructure Evolution and Properties of Sintered Ceramics

Microstructural progress during sintering shapes the final performance of ceramic components. The sintering process creates complex relationships between grain growth, pore elimination, and boundary development that determine material properties.

Grain Growth and Pore Elimination Mechanisms

Sintering creates ongoing competition between densification and grain growth. The energy difference between fine-grained and larger-grained materials drives grain growth. This results from decreased grain boundary area and total boundary energy. Atoms migrate from concave to convex interfaces, which makes grain boundaries move toward their center of curvature.

Different mechanisms control pore elimination at each sintering stage. Tubular pores transform into isolated voids at grain junctions during final sintering stages, typically above 92% theoretical density. Concentration differences between atoms on curved pore surfaces and adjacent grain boundaries drive the shrinkage of these pores.

The dihedral angle and surrounding grain count determine pore stability. Conventional sintering cannot eliminate pores trapped inside grains instead of boundaries. So, controlling grain boundary migration rates is vital to achieve full densification.

Grain Boundary Strengthening and Diffusion Paths

Fine-grained ceramics use grain boundaries as significant diffusion channels. Larger pores than surrounding grains increase diffusion channel count proportionally with pore diameter to grain size ratio. The diffusion channels become independent of this ratio for pores smaller than grains.

The Hall-Petch relationship shows how smaller grains create stronger ceramics. Zinc aluminate ceramics’ Vickers hardness increases from 18.2 to 22.5 GPa when the grain size decreases from 60.3 to 10.1 nm. Grain boundaries block dislocation movement to cause this effect. Some ceramics show remarkable grain boundary strength values of 3.6-6.1 GPa.

Material transport pathways change throughout sintering. Lower temperatures see surface diffusion dominate with a grain growth exponent of about 4. Higher temperatures activate volume diffusion (exponent ≈3) and grain boundary diffusion mechanisms.

Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Strength Correlation

Microstructural characteristics strongly influence thermal conductivity in sintered ceramics. Porosity remains the biggest factor affecting thermal and mechanical properties. Silica ceramics showed total porosity values of 24.4%, 15.6%, and 29.1% at sintering temperatures of 1250°C, 1271°C, and 1300°C. The middle temperature created optimal compactness.

Pore size distribution affects property development more than total porosity alone. Smaller, rounded pores under 5000 µm² with minimal interconnectivity improve crack resistance and compressive strength. Large interconnected pores exceeding 10,000 µm² significantly reduce thermal conductivity and mechanical strength.

Silicon carbide ceramics with 98% theoretical maximum density show exceptional performance. These materials maintain their properties during thermal cycling. Microstructure optimization directly links their thermal conductivity and mechanical strength.

Applications of Sintered Ceramics in Industry

Sintered ceramics have become vital materials in many industries thanks to their outstanding performance and unique properties.

Wear-Resistant Components in Aerospace and Automotive

Ceramic materials shine in automotive and aerospace applications because of their excellent wear and corrosion resistance. Sintered ceramic disks in brake systems help dissipate heat better and reduce brake fade, which makes them more reliable in extreme conditions. Engine components made from ceramics can handle higher temperatures, leading to better fuel efficiency and lower emissions. These ceramic parts hold up well against mechanical stress in racing cars and heavy-duty trucks while maintaining their structure. Modern ceramic sensors now monitor key systems like tire pressure, temperature, and acceleration. They deliver immediate data even in harsh environments.

Bioactive Implants and Porous Scaffolds in Healthcare

Bioactive ceramics create direct bonds with living bone through osteoconduction. Medical implants use hydroxyapatite coatings that combine metal’s strength with ceramic’s biocompatibility. This combination reduces unwanted immune responses. Bone growth works best with porous ceramic supports that have pore diameters around 500 μm. 3D printed ceramic supports give better control over the structure and make production more efficient.

High-Temperature Insulators and Substrates in Electronics

Electronics, especially power modules, rely on high-performance ceramic substrates to manage heat effectively. Aluminum nitride materials conduct heat well while providing excellent electrical insulation. This combination helps components last longer in everything from e-mobility to renewable energy systems. These ceramic insulators work at temperatures up to 3000°F/1650°C and maintain low thermal conductivity.

Conclusion

Sintered ceramics remain the lifeblood of modern manufacturing and connect ancient practices with state-of-the-art innovation. Careful powder selection determines the final product quality through particle size distribution, surface area, and proper additive selection. These early decisions affect every step of the manufacturing process.

Strong components emerge from powder through proper compaction techniques. Cold isostatic pressing creates more uniform density than uniaxial methods. Ceramic injection molding makes complex shapes that traditional methods cannot achieve. The quality of green bodies helps predict how well the final component will perform.

Thermal processing plays a vital role, with tunnel and periodic kilns offering different benefits based on production needs. Notwithstanding that, methods like hot isostatic pressing, spark plasma sintering, and flash sintering have revolutionized manufacturing capabilities. These techniques achieve full densification and preserve nanostructures 1,000 times faster than conventional methods.

A ceramic’s performance relates directly to its microstructural progress during sintering. Grain boundary strengthening, pore elimination mechanisms, and diffusion pathways contribute to exceptional thermal conductivity and mechanical strength. These properties make ceramics valuable across industries.

The remarkable properties of sintered ceramics make them irreplaceable in aerospace, automotive, healthcare, and electronics. These materials show unique versatility and performance in everything from wear-resistant parts that endure extreme conditions to bioactive implants that bond with living tissue.

Manufacturing technology keeps advancing, and sintered ceramics will without doubt keep improving through better process control, new material combinations, and specialized applications. The basic principles in this piece will stay crucial to become skilled at this sophisticated yet adaptable technology.

Key Takeaways

Mastering sintered ceramics requires understanding the complete transformation from powder to high-performance components, with each processing stage critically influencing final product quality and performance.

• Powder characteristics determine everything: Particle size under 1 μm and optimized surface area (20-25 m²/g) create the foundation for successful sintering and superior final properties.

• Advanced techniques slash processing time: Flash sintering achieves densification in under 10 seconds—1,000x faster than conventional methods while preserving nanostructures.

• Microstructure controls performance: Grain boundary strengthening and controlled pore elimination directly determine thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, and component reliability.

• Application versatility drives innovation: From aerospace brake disks to bioactive bone implants, sintered ceramics excel across industries due to exceptional wear resistance and biocompatibility.

The key to successful ceramic manufacturing lies in optimizing each processing stage—from initial powder selection through final sintering—while understanding how microstructural evolution directly translates to real-world performance in demanding applications.

FAQs

Q1. What are the key factors to control during ceramic sintering? The main factors to control during ceramic sintering are time and temperature. These variables significantly influence diffusion rates, which in turn affect the final dimensions, density, shrinkage, and physical properties of the ceramic component.

Q2. What are the three main stages of the sintering process? The sintering process consists of three primary stages: the initial stage (where grain growth begins), the intermediate stage (characterized by shrinkage of pore volume), and the final stage (where grain boundaries form).

Q3. How does sintering affect ceramic materials? Sintering compacts solid ceramic materials through pressure and high heat, causing atoms to bond more tightly. This process results in a stronger, more durable, and harder ceramic mass with improved physical properties.

Q4. What is the typical duration of the sintering process? The duration of sintering can vary widely depending on the specific material and desired properties. Generally, sintering can take anywhere from several hours to several days to complete.

Q5. What advanced techniques are used to reduce ceramic sintering time? Advanced techniques like flash sintering can dramatically reduce processing time. Flash sintering can achieve densification in less than 10 seconds, which is about 1,000 times faster than conventional sintering methods, while also preserving nanostructures in the ceramic material.