Sintered tungsten ranks among the densest metals you can find commercially, with remarkable properties that make it essential in many industries. This heavy metal and its alloys show exceptional density, shield against radiation effectively, and resist high temperatures. These qualities make them vital materials for specialized uses. Most tungsten heavy alloys contain 90-97% tungsten mixed with nickel, iron, and sometimes copper or cobalt through a process called liquid phase sintering.

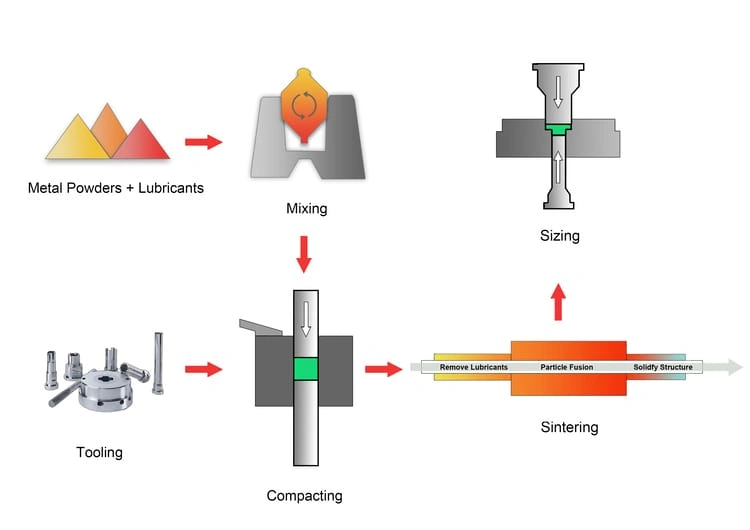

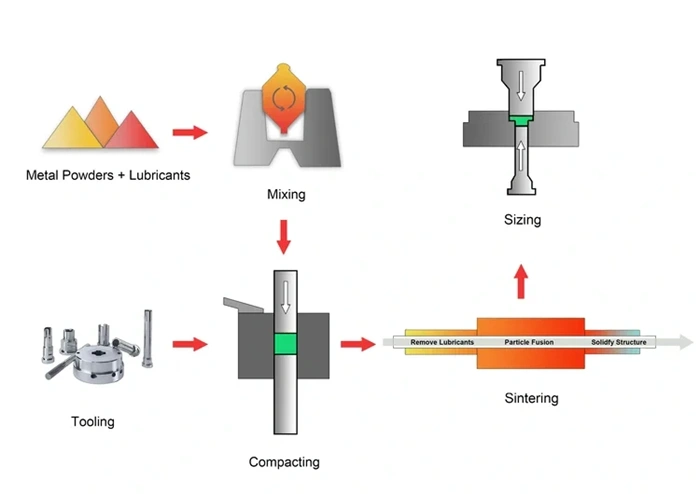

Manufacturing heavy tungsten alloy components requires a sophisticated metallurgical process that turns metal powders into fully dense parts. The tungsten sintering needs precise control of several factors – from powder preparation to compaction techniques and sintering temperatures. The process keeps tungsten particles solid while binder metals melt, which creates a distinct microstructure. This structure gives sintered tungsten alloy its unique blend of strength, machinability, and density. Sintered tungsten carbide components go through similar processing steps but use different binding metals for various applications. This piece walks you through the complete manufacturing process of tungsten heavy alloys. It covers everything from the original powder preparation to final product finishing and highlights the key factors that affect quality and performance.

Powder Preparation for Tungsten Heavy Alloys

The success of tungsten heavy alloy production depends on careful powder preparation. Metal powder blends shape the final properties of sintered tungsten components. This makes powder preparation one of the most vital steps in manufacturing.

Tungsten, Nickel, and Iron Powder Blending Techniques

Blending tungsten with binder metals like nickel and iron needs special techniques because of their density differences. Most tungsten heavy alloys use a nickel-to-iron ratio of 7:3. This ratio creates the matrix that binds tungsten particles during liquid phase sintering.

V-blenders are the industry’s go-to choice for powder mixing. They can handle batches from several hundred kilograms up to one ton at once. A 1,000 kg batch takes about an hour to blend properly. Manufacturers add binders and lubricants to enhance the powder’s properties:

- Binders: PVA and wax-based materials like paraffin help particles stick together

- Lubricants: Materials such as zinc stearate and Acrawax help powder flow better by reducing friction between particles

Some manufacturers use mechanical alloying techniques for advanced applications. Ball milling mixes and grinds tungsten powder with alloy elements thoroughly, which promotes mixing at the atomic level. This process takes time but creates an exceptionally even mix of elements throughout the powder.

Matrix elements can be prealloyed to control melting during sintering. Adding copper to the tungsten-nickel-iron system creates a melting point of about 1080°C. This temperature is much lower than nickel’s 1455°C melting point, which helps matrix elements dissolve gradually as heat increases.

Granular vs Fluffy Powder Characteristics

Tungsten powder’s properties affect how it behaves during processing and the final product’s quality. Manufacturers produce tungsten powder by reducing high-purity tungsten oxides from ammonium paratungstate (APT) with hydrogen. This method creates powders with average grain sizes from 0.1 to 10 μm.

Powder characteristics fall into three groups: chemical (purity), physical (shape, size), and technological (density, flowability). Particle shape plays a big role in how the powder behaves:

Spherical particles mix better because they have less friction between them. They move smoothly through feeders and spread evenly across powder beds. These qualities make them perfect for additive manufacturing. Blending spherical tungsten powders with nano-nickel and iron powders creates better microstructures than irregular powders.

Irregular particles lock together better, which makes stronger green compacts before sintering. This mechanical interlocking improves strength but can make uniform blending harder.

Humidity levels during production affect the powder’s final characteristics. Less humidity creates smaller grain sizes because it changes how metal phases form and how tungsten moves due to volatile compounds.

Screening and Milling for Press Compatibility

Tungsten heavy alloy powders need screening and milling to work well in presses. All powders go through a 200-mesh screen to remove big particles. This creates a more even size distribution and improves how the powder compacts.

Attritor milling can make powder characteristics even better. This method uses tungsten carbide balls to grind particles smaller and create more uniform blends. Small-batch milling can be tricky, but well-milled powders can be 2% denser than standard blends.

Spray drying helps improve powder flow. This process mixes the powder blend with water or organic binders into a slurry, then spray-dries it to create flowable particles. The resulting powder flows at rates between 1 and 15 seconds per 50 grams, making it ideal for automated pressing.

Manufacturers must check that powder characteristics meet specific standards before final processing. These include bulk density (35-65% of theoretical density), tap density (40-75% of theoretical density), and particle size distribution. Meeting these standards ensures consistent results in pressing and sintering operations.

Pressing Techniques in Tungsten Alloy Compaction

The compaction phase plays a key role in creating tungsten heavy alloy components after powder preparation. The choice of pressing technique depends on part size, production volume, and what the final product needs.

Manual Pressing for Large Parts (100–1000 Tons)

Manual pressing operations work best to make big tungsten components because they give you better control and flexibility. These systems use presses that can handle 100 to 1,000 tons (or more). Manual presses work well with “fluffy” powder types that don’t flow well enough for automated systems. Workers load these materials into large molds using special “shovel-type” tools.

Manual pressing shines in specialized applications:

- Better control of compaction settings for complex shapes

- More flexibility when making custom components in small batches

- Lower tooling costs during prototype development

The biggest drawback is output speed – manual systems can only make 1-20 pieces per hour. But for large specialized parts like radiation shields or counterweights, this slower rate is worth it because you get better dimensional control.

Solid die pressing, which makes green ingots for rod, wire, and narrow strip manufacturing, can create compacts up to 2 feet long, 1 inch thick, and 2 inches wide. These compacts go through pre-sintering at 1100°C to 1300°C, then self-resistance sintering until they reach about 90% of theoretical density.

Automatic Pressing: 20–2000 Pieces per Hour

Automatic pressing systems are perfect for small to medium-sized tungsten alloy parts where speed matters most. These systems can make between 20 and 2,000 pieces every hour. The catch is that automatic presses need granular powder formulations that flow smoothly into molds without human help.

Your powder must meet these strict requirements for automatic pressing:

- Flowability: Powder needs to flow smoothly without getting stuck in feed systems

- Uniform particle size: Everything screened and mixed for even die filling

- Adequate lubrication: Right preparation to cut down die wear and make ejection easier

Automatic pressing systems often come with advanced monitoring to keep dimensions consistent during production runs. This feature proves valuable for aerospace components, medical equipment, and automotive parts where every piece needs to match perfectly.

Hydrostatic Pressing with Rubber Molds and Glycerin

Cold isostatic pressing (CIP), also known as hydrostatic pressing, puts equal pressure on all sides at once. Workers start by filling a flexible rubber mold with tungsten powder and sealing it with a cap. The sealed mold goes into a pressure vessel filled with water and glycerin.

The fluid applies pressure evenly throughout the mold, reaching up to 30,000 pounds per square inch. This even pressure distribution brings major benefits:

- Gets rid of density gradients you often see in uniaxial pressing

- Cuts down internal stresses that could cause cracks during sintering

- Stops shear fractures from forming in final castings

CIP lets manufacturers create near-net-shape products with very even density. Advanced applications can use pressure anywhere from 5,000 psi to 100,000 psi (34.5 to 690 MPa). Some facilities even use silicone rubber mold inserts with barrel-shaped chambers inside steel die cavities for special jobs.

All tungsten alloy components shrink quite a bit during sintering, usually 15-18% based on the original pressing pressure. Mold designs must factor in this predictable shrinkage to hit final dimension targets.

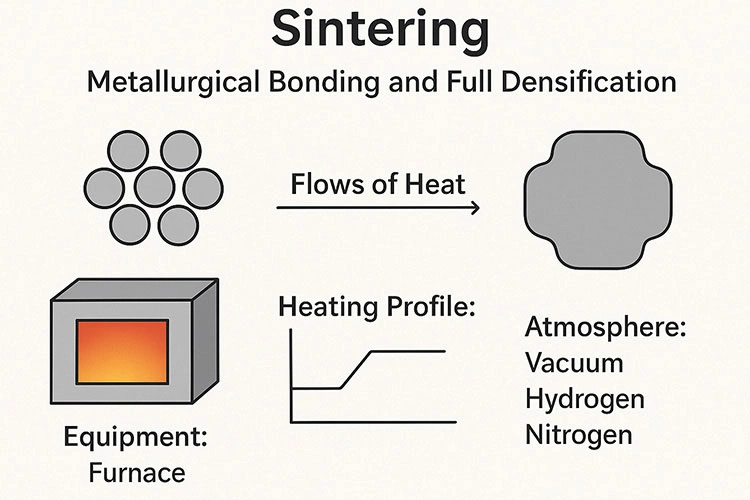

Stages of Liquid Phase Sintering in Tungsten Alloys

Liquid phase sintering is the life-blood of tungsten heavy alloy production. This process turns compacted powder into fully dense components through a carefully coordinated temperature profile across three distinct stages.

Debonding at 900°C to Remove Paraffin

The first sintering phase removes binder materials added during powder preparation. The paraffin wax that holds pressed components together must completely disappear at around 900°C. Temperature must rise between 0.5-1.0°C per minute to ensure precise thermal control. Manufacturers keep dry hydrogen atmospheres with dew points near -55°C to help clean binder removal.

Problems arise in later processing steps without proper debonding. Components won’t sinter correctly if any paraffin stays behind. The process needs holding periods of 30-90 minutes at specific transition temperatures. Several technical methods work well here:

- Vacuum dewax uses low vacuum levels (10^-1 to 10^-2 torr) to evaporate paraffin below its cracking point

- Sweepgas technology uses a graphite retort with inert gas flow to remove vaporized binder

- Positive-pressure flow-through systems use hydrogen or inert gas to clean the chamber of binder buildup

Presintering at 1100°C for Controlled Shrinkage

The temperature rises to about 1100°C after debonding. This middle stage is a vital step that allows gradual shrinkage and prevents distortion. Preliminary particle bonding starts with minimal dimensional changes during presintering. This creates enough structural integrity for the next steps.

Solid-state sintering becomes noticeable at this temperature, especially with nano-tungsten powders that show remarkable reactivity. Specific holding times help promote uniform shrinkage throughout the component. Solid-state diffusion mechanisms cause most shrinkage during this phase instead of liquid formation.

Final Sintering at 1380–1420°C for Full Densification

The last stage happens between 1380°C and 1420°C where liquid phase formation streamlines processes for quick densification. Nickel and iron components melt while tungsten particles stay solid at these high temperatures. Liquid phase formation substantially speeds up diffusion rates. Three overlapping mechanisms drive densification:

- Rearrangement – The wetting liquid creates capillary forces on solid particles that cause quick initial densification

- Solution-reprecipitation – Small particles dissolve first as material moves to larger grains

- Solid-state sintering – More densification happens through diffusion between solid particles

Two minutes at peak temperature is enough to achieve complete densification. Components consistently reach about 96% theoretical density with hardness values near 1700 kg/mm².

The process reduces dimensions by 15-18% from the original pressed size. This shrinkage associates directly with the original compaction pressure—manufacturers use this relationship when designing components. To name just one example, a part starting at 1.0-inch height typically ends up at 0.82-0.85 inches after sintering.

The sintering environment needs careful control. Gravitational conditions substantially affect sintering densification and distortion. Distortion usually happens after densification under normal gravity. However, microgravity sintering might not reach full density even though distortion occurs.

Furnace Design and Atmosphere Control

The right furnace selection and atmosphere management are key factors in tungsten alloy sintering success. Equipment design directly affects production capacity, temperature uniformity, and the final quality of sintered tungsten parts.

Pusher vs Stoker Furnaces for Continuous Sintering

Continuous sintering operations commonly use two main furnace designs: pusher and stoker systems. Pusher furnaces move components through heating zones on boats or plates in a continuous train. The system pauses just long enough to remove a boat at the exit and add one at the entrance. This constant push method gives high production rates without using conveyor belts.

Stoker furnaces work like pusher designs but have slight mechanical differences. Both systems share a big advantage – they don’t have moving parts in high-temperature zones. This lets them work at temperatures from 1200°C to 2200°C. This feature is crucial for tungsten heavy alloy production, which needs sintering temperatures between 1380-1420°C.

Walking-beam furnaces offer an advanced option for specialized applications. These systems use cams that lift, move forward, and lower the boats through the furnace. Components usually move onto cooling belts at the exit to finish the thermal cycle.

Hydrogen and Hydrogen-Nitrogen Atmosphere Effects

The atmosphere’s makeup has a huge effect on sintering quality through several key functions. Sintering atmospheres keep outside air from causing oxidation, help reduce binders in components, lower surface oxide layers, and control carbon content during the process.

Pure hydrogen atmospheres create the best conditions for tungsten sintering through strong reducing capabilities. Manufacturers can also use hydrogen-nitrogen combinations to balance cost and performance. Nitrogen dilutes the hydrogen while keeping enough reducing potential for most applications.

The sintering atmosphere affects the mechanical properties, look, and corrosion resistance of tungsten heavy alloys a lot. Research shows that sintering in a 95% nitrogen/5% hydrogen atmosphere creates higher relative density, better hardness, and better transverse rupture strength (TRS) than vacuum sintering. Parts sintered at 1300°C in nitrogen-hydrogen atmospheres reach 13.6 g/cm³ density, while similar parts in vacuum only reach 12.3 g/cm³.

TRS values show similar differences. Parts sintered at 1300°C in nitrogen-hydrogen atmospheres show about 1320 MPa strength, going up to 1680 MPa at 1400°C. Vacuum-sintered parts at the same temperatures only reach 617.6 MPa and 1383 MPa.

Molybdenum Boat Loading and Throughput Rates

Sintered tungsten components need special handling containers during thermal processing. Molybdenum boats are the standard carriers, usually 8 inches wide by 18-24 inches long. These special containers can handle extreme temperatures without contaminating the tungsten parts.

Continuous sintering operations usually process one boat per hour, pushing 24 boats through the furnace daily. Each molybdenum boat holds 8-10 kg of tungsten alloy components. This sets production capacity limits for continuous operations.

Loading density plays a crucial role in processing. Overloaded boats create temperature differences within the load, which can cause uneven sintering results. Good loading practices ensure even temperatures throughout the sintering cycle.

Batch furnaces provide an alternative to continuous systems for smaller production runs. They offer lower throughput but give more flexibility for specialized components. Models like CM 1500 and CM 1700 hydrogen atmosphere batch furnaces can sinter and debind in one step at temperatures up to 1700°C. This removes the need for separate processing stages.

Shrinkage and Dimensional Control in Sintered Tungsten Alloy

Dimensional changes in tungsten alloy sintering happen in predictable ways, but manufacturers need to manage them carefully. The process requires accounting for substantial shrinkage while meeting exact specifications for finished components.

15–18% Shrinkage Based on Original Press Pressure

The basic shrinkage patterns of sintered tungsten alloys start with the pressing process. Parts shrink by 15-18% during sintering, and this reduction directly relates to the original compaction pressure. A component pressed to 1.0-inch height will typically end up between 0.82-0.85 inches after complete sintering. Manufacturers can design oversized components that will reach their target dimensions after heat treatment because they know these patterns.

Pressure applied during compaction plays a key role in determining final shrinkage rates. Dense green compacts with less void space result from higher original pressures, which leads to slightly lower shrinkage percentages. At the microscopic level, pressure reduces the space between powder particles, which creates more contact areas and stronger diffusion paths during densification.

Rough Oversize to Finish (ROTF) Strategy

Manufacturers produce components as “Rough Oversize To Finish” (ROTF) blanks because of these substantial dimensional changes. This method adds extra material to each dimension for later machining operations. Customers can receive ROTF parts either as-sintered or partially machined.

Each ROTF order needs individual evaluation to pick the best die that provides enough machining stock without wasting material. Manufacturers base their quotations on approximate dimensions using the most suitable die available. They can machine parts to specific dimensions and tolerances before delivery if the approximate dimensions leave too much extra material.

Challenges in Achieving Final Dimensional Accuracy

Getting precise dimensional control in sintered tungsten alloy components comes with several technical hurdles:

- Uneven shrinkage across dimensions makes prediction difficult, which makes the ROTF approach necessary

- Gravitational effects affect both densification and potential distortion during sintering

- Sintering parameters like temperature, time, and atmosphere substantially affect dimensional results

- Initial powder characteristics affect shrinkage behavior and final dimensional accuracy

Distortion often happens after densification completes under normal gravity conditions. In contrast, parts sintered in microgravity might not reach full density even though they experience distortion. This shows the complex relationship between densification mechanisms and dimensional stability.

Temperature control plays a crucial role in dimensional accuracy. Manufacturers can meet tight tolerances and ensure assembly compatibility by managing sintering parameters carefully. The whole thermal cycle from debinding through final sintering needs precise control to maintain dimensional consistency in tungsten heavy alloy components.

Post-Sintering Treatments and Final Product Characteristics

Raw tungsten alloy components become precision-engineered products through specialized post-processing operations after complete sintering.

Surface Finishing from ROTF Blanks

The manufacturing process creates sintered components as “Rough Oversize To Finish” (ROTF) blanks. These blanks come with extra stock of about 0.060 inches per dimension. The components then go through precision finishing operations like tumbling to polish and smooth their surfaces. Grinding operations help achieve strict dimensional tolerances, especially for spherical and cubic shapes. The final step involves ultrasonic and chemical cleaning to remove any leftover contaminants.

Mechanical Properties of Sintered Tungsten Alloy

Post-sintering heat treatments reshape the mechanical properties of tungsten alloys. These processes include quenching, dehydrogenizing, and surface hardening. They reduce hydrogen embrittlement and enhance tensile strength and ductility. Well-processed tungsten alloys deliver these consistent results:

- Density: ≥17.2 g/cm³

- Tensile strength: ≥650 MPa

- Elongation: ≥3%

- Surface hardness: 24-33 HRC

Deformation processing can push ultimate strengths up to 1350 MPa, with hardness values reaching 450 HV10 [16].

Applications in Radiation Shielding and Aerospace

Tungsten heavy alloys serve as excellent radiation shields in many industries. Medical equipment uses them to absorb harmful radiation during therapy and diagnostic imaging. These materials protect aerospace crew and passengers from radiation exposure. On top of that, W-Re alloys work well in high-temperature engine parts like turbine blades. W-Ni-Cu alloys, with their thermal conductivity of about 150 W/m·K, manage heat effectively in critical systems.

Conclusion

Tungsten heavy alloys are unique materials that offer high density, excellent radiation shielding, and resistance to high temperatures. These properties come from specific manufacturing techniques based on liquid phase sintering. The process keeps tungsten particles solid while binder metals like nickel and iron melt. This creates special microstructures with a mix of unique properties.

The quality of tungsten alloy components depends on proper powder preparation. The right blending techniques, particle characteristics, and screening methods improve the final product by a lot. Manufacturers must choose the best pressing techniques based on their production needs. Manual pressing works well for large specialized components, while automatic systems suit high-volume production.

The liquid phase sintering process follows specific temperature stages that manufacturers arrange with care. The process starts with debonding at 900°C to remove paraffin binders. Next comes presintering at 1100°C that allows controlled shrinkage. The final sintering happens between 1380-1420°C to achieve complete densification. Furnace design and atmosphere control are crucial. Hydrogen or hydrogen-nitrogen atmospheres create the best conditions for tungsten sintering.

Manufacturing these alloys comes with its share of challenges. The material shrinks 15-18% during sintering, which makes dimensional control tricky. Manufacturers use the Rough Oversize to Finish (ROTF) strategy to solve this. They add extra material that they can machine later.

Post-sintering treatments turn raw tungsten alloy blanks into engineered products with exceptional mechanical properties. These materials reach densities above 17.2 g/cm³, tensile strengths over 650 MPa, and surface hardness between 24-33 HRC. These features make tungsten heavy alloys essential in specialized applications, especially when you have radiation shielding and aerospace components.

The manufacturing process shows how controlling metallurgical variables creates materials with extraordinary performance. Without doubt, better production techniques will improve tungsten alloys’ capabilities even more. This will expand their use in industries that need materials with extreme properties.

Key Takeaways

Liquid phase sintering transforms tungsten powder into dense, high-performance alloys through precise temperature control and metallurgical expertise, creating materials essential for radiation shielding and aerospace applications.

• Three-stage sintering process: Debonding at 900°C removes binders, presintering at 1100°C controls shrinkage, and final sintering at 1380-1420°C achieves full densification through liquid phase formation.

• Predictable 15-18% shrinkage: Components shrink consistently during sintering based on initial press pressure, requiring “Rough Oversize to Finish” strategy for dimensional accuracy.

• Powder preparation is critical: Proper blending of tungsten with nickel-iron binders (7:3 ratio) and screening through 200-mesh determines final component quality and performance.

• Atmosphere control ensures quality: Hydrogen or hydrogen-nitrogen atmospheres prevent oxidation and enable superior mechanical properties compared to vacuum sintering.

• Exceptional final properties: Sintered tungsten alloys achieve densities ≥17.2 g/cm³, tensile strengths ≥650 MPa, and surface hardness of 24-33 HRC for demanding applications.

The success of tungsten alloy production depends on mastering each manufacturing stage, from initial powder characteristics through final thermal processing, to achieve the extraordinary material properties required for specialized industrial applications.

FAQs

Q1. What is liquid phase sintering and why is it important for tungsten alloys? Liquid phase sintering is a critical process in tungsten alloy production where tungsten particles remain solid while binder metals like nickel and iron melt. This creates a unique microstructure that gives sintered tungsten alloys their exceptional combination of density, strength, and radiation shielding properties.

Q2. How much shrinkage occurs during the sintering of tungsten alloys? Tungsten alloy components typically experience 15-18% shrinkage during sintering. This predictable reduction is directly related to the initial compaction pressure applied during pressing. Manufacturers account for this shrinkage by producing oversized components that achieve desired final dimensions after thermal processing.

Q3. What are the key stages in the sintering process for tungsten alloys? The sintering process for tungsten alloys involves three main stages: debonding at 900°C to remove paraffin binders, presintering at 1100°C for controlled shrinkage, and final sintering between 1380-1420°C for full densification. Each stage serves a specific metallurgical function in transforming the powder compact into a dense component.

Q4. Why is atmosphere control important during tungsten alloy sintering? Proper atmosphere control, typically using hydrogen or hydrogen-nitrogen mixtures, is crucial during sintering to prevent oxidation, reduce surface oxides, and optimize mechanical properties. Sintering in these controlled atmospheres yields higher density, improved hardness, and enhanced strength compared to vacuum sintering.

Q5. What are some common applications for sintered tungsten alloys? Sintered tungsten alloys are widely used in radiation shielding applications, particularly in medical equipment for radiation therapy and diagnostic imaging. They are also utilized in aerospace components, serving as protective materials against radiation exposure and in high-temperature engine parts like turbine blades due to their exceptional density and thermal properties.