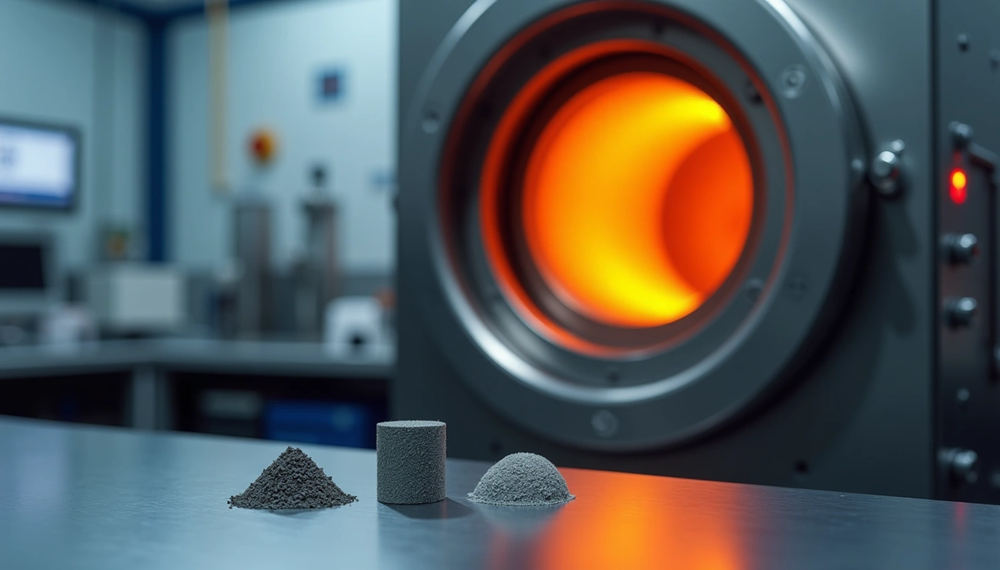

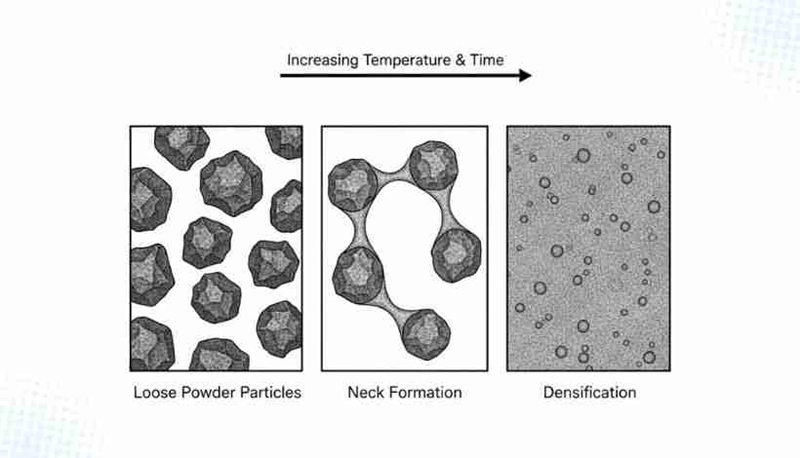

Solid-state sintering changes loose powder particles into densified components through a remarkable thermal process. The process heats powders below their melting point, which allows particles to bond without liquefaction . Traditional solid-state sintering processes create components with many voids and densities below 90% of theoretical values, making optimal density hard to achieve . The densification happens because surface free energy decreases as the internal surface area of pores gets eliminated .

Solid state sintering moves through distinct stages that create specific changes in microstructure. Interparticle necks start forming between neighboring particles and grow larger as particle centers come closer . The material enters its final development phase once density reaches about 92% of theoretical density . The success of densification relies on transport mechanisms like grain boundary diffusion, surface diffusion, and lattice diffusion . Materials engineers working with powder metallurgy technology and metal injection molding applications need to understand these mechanisms. This piece explores the foundations of solid state sintering and gets into the key differences between solid state and liquid phase sintering techniques.

Fundamentals of Solid-State Sintering Process

Solid-state sintering serves as the lifeblood technique in powder metallurgy manufacturing. This method transforms powder materials into robust components through controlled heat treatment, unlike traditional melting processes.

Definition and temperature range of solid-state sintering

Solid-state sintering uses heat treatment on powders or powder compacts at high temperatures that stay below the melting point of the materials. The process happens completely in a solid state, and no liquid phase forms during densification. The temperature usually ranges from 70% to 90% of the material’s melting temperature (0.7-0.9 Tm). This range provides enough heat energy to activate diffusion mechanisms without melting the material.

The temperature range plays a significant role because atoms become mobile enough to bond while the powder compact’s structure remains intact. To name just one example, ceramic manufacturing of UO2 fuel pellets needs sintering at about 1700°C for several hours. This continues until the material reaches over 95% of its maximum theoretical density. Metal powder applications in powder metallurgy work best when the sintering temperature stays between 60-70% of the melting temperature.

Thermodynamic driving force: surface energy reduction

The basic thermodynamic force that powers solid-state sintering reduces the total surface free energy in the powder system. This energy drops through two main mechanisms:

- Lower-energy solid-solid interfaces (grain boundaries) replace high-energy solid-vapor interfaces (particle surfaces)

- Total surface area decreases as particles join together

Powder particles exist in an unstable, high-energy state because of their huge surface area from a thermodynamic view. The system naturally tries to minimize this excess energy by joining particles, which creates a more stable structure with less total free energy. The mathematical expression of this force then involves reducing γA, where γ represents specific surface energy, and A shows the total surface area of the compact.

The driving force reaches its peak at contact points between particles, where small concave “necks” form. Atoms on convex surfaces have a higher chemical potential than those in concave neck regions. This creates a curvature gradient that pushes diffusion toward growing neck areas.

Difference between solid-state sintering and liquid-phase sintering

Solid-state sintering is different from liquid phase sintering in several important ways:

- Phase State: Solid-state sintering happens entirely in the solid phase below the material’s melting point. Liquid phase sintering uses a liquid phase that coats solid primary particles.

- Temperature Range: Solid-state sintering works at 0.7-0.9 Tm. Liquid phase sintering needs higher temperatures (0.8-0.98 Tm) for partial melting.

- Transport Mechanisms: Solid-state sintering mainly uses atomic diffusion through surface, grain boundary, and volume diffusion paths. Liquid phase sintering uses liquid flow that enables rearrangement and solution-precipitation mechanisms.

- Densification Rate: Solid-state sintering densifies slowly through diffusion mechanisms. Liquid phase sintering moves faster because of liquid flow assistance.

- Microstructure: Solid-state sintering creates finer, more uniform grains with high dimensional stability. Liquid phase sintering tends to produce coarser grains with possible segregation or distortion.

Metal injection molding (MIM) and other powder metallurgy applications choose between these methods based on material needs, desired properties, and production factors. Solid-state sintering gives benefits like stable shape retention, clean microstructure, and strong bonding. These qualities make it perfect for structural components, gears, and bushings. Notwithstanding that, liquid phase sintering offers easier microstructure control and potentially lower processing costs, though sometimes mechanical properties might suffer.

Atomic Transport Mechanisms in Solid-State Sintering

Mass transport at the atomic level drives the solid-state sintering process. Manufacturers can control densification, microstructure progress, and the performance of powder metallurgy components by understanding these mechanisms.

Grain boundary diffusion and its role in densification

Grain boundary diffusion is the main densifying mechanism in solid-state sintering. This is particularly true for fine powders processed at lower temperatures. Grain boundaries serve as efficient vacancy sinks or diffusion paths for lattice vacancies when powder particles connect. Atoms flow from the grain boundary to the neck region because of chemical potential differences between these areas.

Grain boundaries’ configuration affects sintering rates. Atoms diffuse from the grain boundary to the neck surface. This creates compressive stresses in the grain boundary while the neck region develops tensile stresses. Such a stress gradient helps material transport and enables particles to move closer together—a vital characteristic of true densification.

Grain boundary diffusion becomes more dominant as grain size and temperature decrease. Vacancies disappear at the grain boundaries through this mechanism. This allows particle centers to move closer, which makes the powder compact shrink.

Surface diffusion and coarsening effects

Surface diffusion is a non-densifying transport mechanism that moves atoms across particle surfaces toward neck regions. It adds to neck growth but doesn’t help densification. Material just moves along existing surfaces instead of filling pore spaces.

This mechanism works against densification by causing coarsening. This process reduces the driving force needed for densification. The pressure gradient at curved surfaces, described by ΔP=2γ/R (where γ is surface energy and R is radius of curvature), drives both coarsening and densification at the same time.

Surface diffusion leads the process in early sintering stages, particularly at lower temperatures. This happens because it needs less activation energy than other mechanisms. Metal injection molding component manufacturers must control surface diffusion with proper heating rates. This prevents early coarsening that could reduce final density.

Lattice diffusion and vacancy migration

Lattice diffusion moves vacancies through crystal lattices, following D∝cvexp(–Em/kT), where cv represents vacancy concentration. This mechanism can either help densification or cause coarsening based on where material comes from.

Material doesn’t densify when vacancies flow from neck surfaces to particle interiors. Atoms move from particle centers toward necks. However, lattice diffusion helps densification when vacancies migrate from necks to grain boundaries.

Lattice diffusion changes with lattice irregularity. This explains why quenched metals with excess vacancy concentrations (≈104) show better diffusion at low temperatures. Manufacturers can optimize processing parameters by understanding these effects.

Plastic flow and dislocation motion in metal powders

Scientists still debate plastic deformation in solid-state sintering. Yet, evidence shows that dislocation generation and movement help densification in metal powders.

Plastic flow starts when stresses at particle contacts exceed the material’s yield strength. This causes permanent deformation as dislocations move. High local stresses from large interface curvatures (scaling with γ/r) can trigger localized plastic deformation in metals.

Temperature affects how easily dislocations move. This influences the boundaries between cold, warm, and hot deformation regimes. Scientists have found many dislocations within grains after sintering certain ceramic systems. These create pinning sites that change mechanical and electrical properties.

These four transport mechanisms work together during solid-state sintering. Their impact varies with temperature, particle size, and processing conditions. Successful powder metallurgy manufacturing needs a balance of these mechanisms. This achieves the best densification while limiting unwanted microstructural changes.

Stages of Solid-State Sintering in Powder Metallurgy

Powder metallurgy components go through distinct physical changes during heating. Each transformation has unique characteristics and material behaviors. These phases shape the solid-state sintering process and determine the final material properties and performance.

Original stage: neck formation and contact area growth

The process starts as heating begins when powder particles create contact points and form small “necks” between them. Atomic transport and surface diffusion mechanisms drive this neck formation. The particle centers stay in their original positions at this point, so no major dimensional changes or density increases occur.

The coordination number of particles rises as necks grow until the material reaches about 75% relative density. Most pores stay connected and create an open network throughout the compact. Curved particle surfaces drive neck growth as atoms move from convex regions toward concave neck areas.

Particles that connect face-to-face merge in classic fashion. However, particles joining along cube corners or edges might develop unstable necks. These necks grow at first but can break later, which leads to “de-sintering”. This phase builds the foundation for future densification by maximizing the contact area between particles.

Intermediate stage: pore channel shrinkage and grain rearrangement

The intermediate stage begins when adjacent necks start to merge. Necks grow larger and grains begin to expand during this vital phase. These changes reduce porosity and increase density. The pore structure changes into connected cylindrical channels that mainly form along three-grain junctions.

The material becomes denser as these pore channels get smaller in diameter. Lattice diffusion and grain boundary diffusion transport material and steadily reduce pore volume. The pores become rounder as heating continues, and some move away from grain boundaries.

The microstructure develops into polyhedral grains with pores mainly at three-grain edges by the end of this stage. The compact reaches about 93% relative density before moving to the final stage. Research shows that intermediate stage sintering often creates uneven densification rather than uniform shrinkage.

Final stage: pore isolation and grain growth

Pore channels break up into isolated pores at four-grain junctions when density reaches about 92% of theoretical density. This marks the start of the final stage. The remaining pores become more spherical as the system tries to minimize interfacial energy. Pore isolation changes how densification happens because gas must now diffuse through the solid matrix to eliminate pores completely.

Grain growth speeds up in this last phase. This creates challenges for complete densification because larger grains mean longer diffusion paths, which slow down sintering. Materials with trapped gasses in pores might never reach full density.

The surrounding matrix must deform through grain boundary sliding and diffusion to shrink large pores. Full densification needs a 40-50% volume reduction. This can only happen when grain boundary sliding occurs while powder particles keep their equiaxed shapes.

Metal injection molding components made through powder metallurgy need careful control of these final-stage events. This balance helps optimize mechanical properties since too much grain growth can reduce strength and toughness. Manufacturers can create optimal microstructures with minimal porosity by controlling time, temperature, and atmosphere.

Sintering Stress and Curvature-Driven Densification

Surface curvatures create stress fields that power particle bonding in sintering. Engineers use this knowledge to make powder metallurgy applications more dense.

Laplace pressure and sintering stress equations

Sintering stress is the internal force that makes powder compacts more dense. This stress balances surface tension forces to prevent further shrinkage in equilibrium states. Scientists have developed three ways to calculate sintering stress: the energy difference method, the curvature method, and the force balance method [1].

The Laplace equation forms the foundations of sintering stress by measuring local pressure differences across curved interfaces. You can express local sintering stress (L) as:

L = γ × (1/R₁ + 1/R₂)

Here, γ represents interfacial energy, while R₁ and R₂ are the principal radii of curvature at the surface. Both radii are similar for spherical particles and the geometric constant equals 1.

The energy difference method follows thermodynamic principles and measures total energy change through virtual pore volume reduction. The curvature method takes a direct approach by calculating stress from surface geometry. All three methods give similar results for idealized porous materials with constant surface curvature.

Grain boundary energy plays a big role in sintering stress and affects how stable porous structures are at different temperatures. The curvature method includes this contribution in a secondary term that combines surface energy and grain boundary energy effects.

Effect of particle size and shape on stress gradients

Particle size has a huge impact on sintering stress and densification. Herring’s scaling law shows that sintering time changes with particle size. Under similar conditions, 10 nm particles reach the same density levels 10⁶-10⁸ times faster than 1 μm particles.

Larger particles create less sintering stress. Materials with smaller particles create stronger driving forces at high temperatures because they have larger surface areas. This helps small-particle materials reduce pores more quickly and create denser structures.

A particle’s shape changes how stress spreads through the sintering compact. Spherical particles are stronger after sintering than rod-like or disk-like particles. This happens because spherical shapes spread loads evenly across many grain boundaries. Rod-like or disk-like particles concentrate loads on fewer grain boundaries and break more easily under pressure.

These effects go beyond just mechanical properties. Materials with smaller, more spherical particles show fewer high-strain areas in simulations, which shows better internal stress spread. Satellite particles speed up the process by increasing curvature near sintering necks. This boosts sintering driving stress and helps make materials denser.

The packing density changes a lot based on particle shape. Rod-like particles pack to only 33.5% density compared to 62.3% for disk-like and 61.0% for spherical particles. But rod-like particles can still reach 94.3% relative density at 1600°C with the right sintering approach.

Powder metallurgy manufacturers can create ideal microstructures by controlling these stress-related factors carefully. This works for everything from medical implants to aerospace parts.

Influence of Process Parameters on Densification

Process parameters act as control levers that determine final properties in solid-state sintering. Engineers need to become skilled at using these variables to achieve optimal microstructure and density in powder metallurgy components.

Sintering temperature and heating rate

Temperature plays a vital role in densification during solid-state sintering. Powder particles transform from poor mechanical bonding to strong metallurgical connections as sintering temperature rises, and internal pores become smaller or disappear completely. The Arrhenius diffusion coefficient equation explains this relationship, and densification speeds up with temperature increases.

Research data shows this relationship clearly. A study of Al-based alloy revealed that sintered density increased faster from 2.73 g/cm³ (93.49% relative density) to 2.8 g/cm³ (95.89% relative density) when sintering temperature went from 560°C to 640°C. The density gains slowed down between 640°C and 700°C, with only a slight increase to 2.81 g/cm³ (96.23%).

In spite of that, higher temperatures don’t always produce better results. Serious deformation can occur when sintering temperature approaches the material’s melting point (658°C for the Al alloy), which compromises the near-net-shape advantages of powder metallurgy manufacturing. Other materials follow similar patterns—Ti/TiB composites showed increased densification rates at higher temperatures between 1250°C and 1350°C.

Heating rate selection creates a crucial tradeoff. Undesirable effects can occur with slow heating rates (0.2-0.5°C/min), as aluminum nitride formation reaches up to 30 vol.% at these rates. Faster heating suppresses surface diffusion, which typically dominates at low temperatures due to its lower activation energy.

Ultra-high heating rates (1200°C/s) showed remarkable improvements in many ceramic materials’ densification compared to conventional rates. Most porosity sites disappeared within one minute at 1200°C under ultra-high heating conditions, while slowly heated samples kept significant porosity even after 30 minutes.

Atmosphere control and its effect on oxidation

Sintering atmosphere affects densification by controlling oxidation and reduction reactions. Atmosphere distribution should be zoned for optimal results: about 20% wet or dry nitrogen in the pre-heat zone, 60% nitrogen+hydrogen mixture in the hot zone, and 20% dry nitrogen in the cooling zone.

Hydrogen breaks down surface oxides that would block particle bonding, making it a powerful reducing agent. Nitrogen works as a cover gas—as with water protecting material while hydrogen acts like soap cleaning away oxides. This combined atmosphere can achieve dew points below -60°C.

A dew point’s temperature directly shows reducing potential—lower dew points mean stronger reducing conditions. Materials containing elements with strong oxygen affinity, like chromium, just need more aggressive reducing atmospheres.

Atmosphere requirements change across specific sintering zones. The pre-heat zone often requires slightly oxidizing conditions to remove lubricant, while the high-heat zone needs reducing conditions to eliminate particle surface oxides. Precise control happens through zirconia-based oxygen probes that adjust hydrogen flow rates based on measured oxidizing/reducing potential.

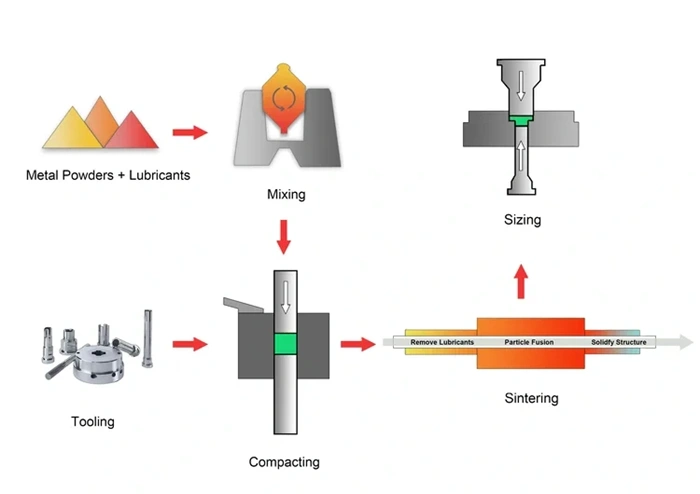

Compaction pressure and green density

Green density of powder compacts depends directly on compaction pressure, which is a big deal as it means that final sintered properties are affected. Material types determine pressure requirements—softer metals like aluminum need lower pressures (200-400 MPa) compared to harder materials such as steel (400-800 MPa).

Particle deformation and rearrangement determine compaction pressure. A study showed that sintered density increased by 0.05 g/cm³ (2.11% relative density) when compaction energy rose from 1325J to 1885J. Higher pressure creates larger particle contact areas, which helps subsequent sintering densification.

Green density distribution follows clear patterns. The specimen center shows highest relative density, which decreases toward die-powder or punch-powder boundaries. Final sintered properties and dimensional precision depend on this density gradient.

Lubricants improve density and compressibility by filling gaps between powder particles during compaction. They reduce friction and wear on tooling components too. Careful control of pressure application speed affects both green density and structural integrity.

Advanced Solid-State Sintering Techniques

New technologies have emerged to improve solid-state sintering efficiency and outcomes beyond conventional methods. These techniques solve traditional problems and deliver better densification, faster processing, and improved material properties.

Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) for rapid densification

Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS), also known as Field Assisted Sintering Technique (FAST), has changed how we consolidate powder through simultaneous application of pulsed direct current and uniaxial pressure. This technique creates internal Joule heating at rates up to 1000°C/min, which allows processing at temperatures 200-500°C lower than conventional sintering methods. SPS achieves complete densification in just 5-10 minutes under moderate pressure (typically 0.15 GPa maximum), compared to several hours with traditional approaches.

SPS’s efficiency comes from its unique heating mechanism. The electrical current flows through both the graphite mold and powder sample. This creates ultra-fast heating while keeping nanoscale structures intact that would otherwise coarsen during longer heating cycles. Market projections show SPS technology will reach $1.83 billion by 2030.

Microwave sintering for energy-efficient processing

Microwave sintering stands out as another breakthrough with its unique volumetric heating mechanism. Unlike traditional techniques that heat from outside in, microwave energy turns directly into thermal energy within the material. This key difference allows heating rates up to 100°C/min while using less energy.

Metal powders work surprisingly well with microwave sintering, even though bulk metals reflect microwaves. Components produced this way are up to 60% stronger than those made with conventional methods. The process works because powdered metals absorb microwaves at room temperature and generate heat effectively. Aluminum-based composites reach optimal results at 695°C with microwave processing, compared to 735°C with conventional methods.

Hot pressing and hot isostatic pressing (HIP)

Hot pressing combines high temperatures (up to 2400°C for ceramics) with uniaxial pressures between 30-50 MPa. This single-step process applies heat and pressure at the same time. It speeds up densification and prevents grain growth. Hot pressing runs at temperatures 150-200°C lower than conventional sintering for temperature-sensitive applications.

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) builds on this idea by using inert gas to apply uniform pressure in all directions. HIP works at pressures up to 207 MPa (30,000 psi) and temperatures up to 2000°C, removing almost all porosity. Parts made this way have near-theoretical density with better fatigue strength, tensile ductility, and fracture toughness. HIP technology costs have dropped by 65% in the last two decades, making it a practical choice for precision powder metallurgy applications.

Microstructure Evolution and Grain Growth Control

Scientists face a key challenge in powder metallurgy: controlling grain growth in sintered materials. Research teams have developed strategies that work to manage how microstructures change during heat treatment.

Role of dopants in grain boundary pinning

Dopants change grain growth kinetics by segregating at grain boundaries. These additives create elastic effects from size mismatches and electrostatic effects from charge differences in ceramic systems. Y³⁺ ions spread across zirconia grain boundaries with a width of 4–6 nm, which slows down growth rates.

La³⁺ doping in yttria shows slower grain growth kinetics than Gd³⁺ doping. La’s size mismatch with the host lattice explains this difference. This mismatch makes La³⁺ segregate at boundaries, while Gd³⁺, which has no size mismatch, barely segregates. The solute drag effect slows down grain boundary migration rates.

Solubility levels determine segregation strength. Y₂O₃ has much lower solubility in Al₂O₃ (about 10 ppm) compared to TiO₂ (a few mol ‰). This leads to stronger grain boundary segregation effects with Y₂O₃. Manufacturers now use these properties to fine-tune microstructures in powder metallurgy components.

Zener pinning and second-phase particles

Second-phase particles block grain boundary migration through Zener pinning. This follows the relationship D = K(r/f^m), where D is matrix grain size, r means particle radius, f shows volume fraction, and K and m are constants.

Particle characteristics affect pinning effectiveness:

- Size: Smaller particles pin better—10% volume fraction of 10 nm particles gives grain growth exponents of 9.0, compared to 5.3 for 300 nm particles

- Morphology: Needle-shaped particles work better than circular ones, with aspect ratios far from 1.0 showing better pinning

- Distribution: Uniform particle distribution gives the best pinning effects

Scientists have found a critical particle size (200 nm at 10% volume fraction). Below this size, pinning effects increase dramatically. Pinning force grows with the ratio of particle content to size, which makes small particles at higher volume fractions excellent at controlling grain growth.

Ostwald ripening and abnormal grain growth

Ostwald ripening happens when bigger grains grow while smaller ones shrink through long-range diffusion. Scientists call this process phase coarsening. It increases average grain size and reduces total interfacial energy. Solution-reprecipitation drives this mechanism in fully wetting systems after densification ends.

Abnormal grain growth (AGG) occurs when certain grains expand faster than their neighbors. Three main factors cause this: high concentrations of second-phase precipitates, big differences in interfacial energy, or significant chemical inequilibrium.

Specific grain boundary structures often trigger this mechanism, which gives growth advantages to certain orientations. Second-phase particles can either stop or encourage abnormal growth based on their distribution. Particle coarsening during heat exposure reduces the Zener pinning force proportionally to particle radius. This change allows abnormal growth in structures that were stable before.

Powder metallurgy manufacturers can engineer precise microstructures by choosing the right processing parameters, dopants, and second-phase particles based on these mechanisms.

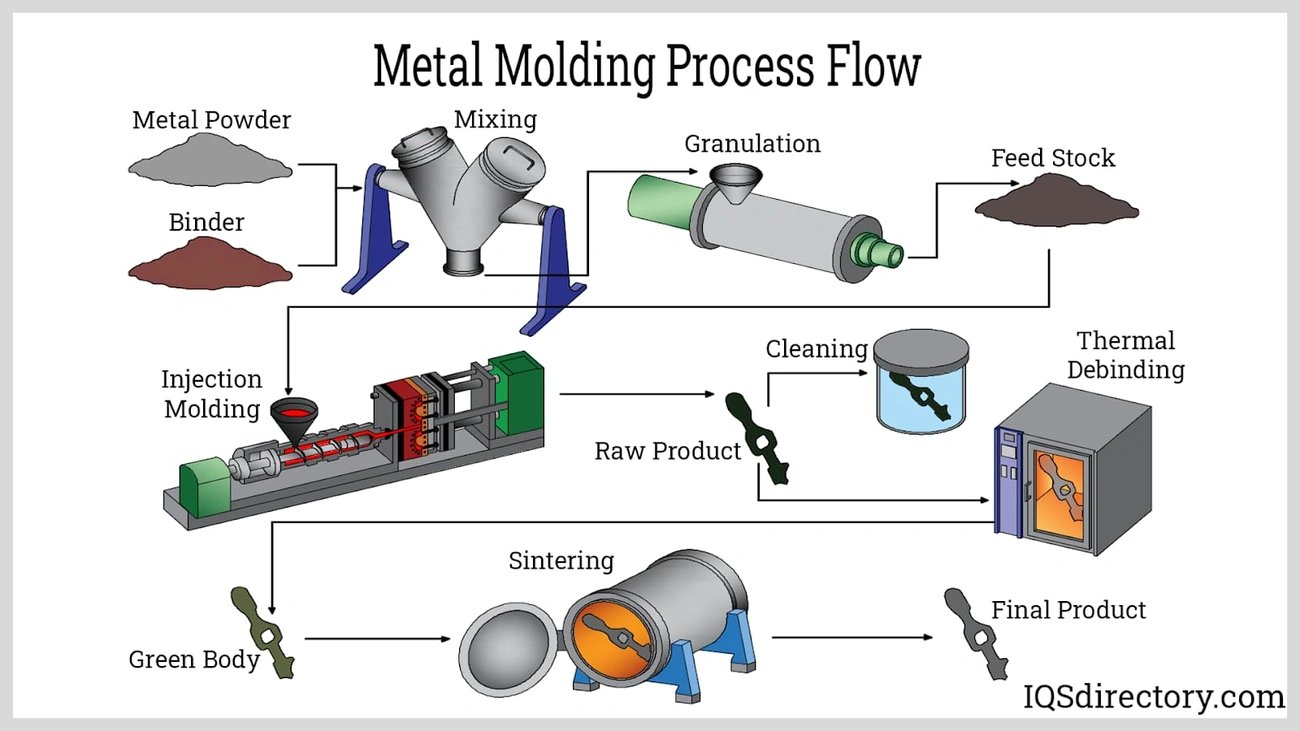

Applications in Metal Injection Molding and Powder Metallurgy

Metal Injection Molding (MIM) stands out as one of the most practical ways to apply solid state sintering principles when manufacturing complex components. This technology has become a quickest way to produce parts in the last decade.

Solid-state sintering in MIM for complex geometries

MIM depends on solid state sintering as its final vital step to turn fragile “brown parts” into strong, high-density components. The parts heat up under controlled conditions just below the metal’s melting point. MIM helps create intricate geometries with undercuts, thin walls, and internal cavities while maintaining material integrity. Many industries benefit from this technology, including machining, medical, electronics, security, watchmaking, and sheet metal processing. Solid-state sintering in MIM applications builds optimal strength through several significant stages. These stages remove remaining binder materials, reduce surface oxygen, and develop sintered necks between metal particles.

Use in high-performance ceramics and hardmetals

Solid-state sintering is a great way to get results for high-performance materials. The process creates electromagnetic ceramic components for capacitors, insulators, and laser materials. Structural ceramics made this way become cutting tools, biomedical implants, and engine components with better thermal resistance. On top of that, scientists have developed energy-efficient microwave cold sintering processes. This is a big deal as it means that energy use drops by 97% while mechanical and dielectric properties improve by 50-95%.

Case study: densification of WC-Co and Fe-Cu systems

WC-Co hardmetals show remarkable solid-state densification properties. Complete densification happens between 1150°C and 1230°C—below Co’s eutectic melting point. The final microstructure shows a bimodal cobalt distribution with thin layers between tungsten carbide grains and small cobalt pools about 1 μm wide. These microstructural features lead to better hardness (over 2000 HV10 units) and fracture toughness. Fe-Cu-Co-Ni-W-Sn powder systems also show distinct densification stages. The original solid-state densification occurs between 800°C and 1190°C, mainly because of grain growth mechanisms.

Conclusion

Solid state sintering serves as the lifeblood of powder metallurgy. This technology turns loose powder particles into densified components through controlled thermal processing below the material’s melting point. The process combines various transport mechanisms—grain boundary diffusion, surface diffusion, lattice diffusion, and plastic flow—to create strong interparticle bonds. These mechanisms shape the final properties of sintered components through their unique contributions to densification and microstructural development.

The process moves through three key stages: original neck formation, intermediate pore channel shrinkage, and final pore isolation. These stages mark crucial shifts in microstructural development. Without doubt, manufacturers can optimize processing parameters for specific applications by understanding these stages. Surface energy reduction and curvature effects create sintering stress, which provides the basic thermodynamic force behind densification. Particle size and shape substantially affect stress distribution and densification rates.

Temperature, heating rate, atmosphere, and green density have dramatic effects on densification outcomes. Diffusion rates speed up at higher temperatures, while controlled atmospheres stop oxidation from interfering with particle bonding. Manufacturers must balance these parameters carefully to achieve the best microstructures without losing dimensional stability.

Modern techniques like Spark Plasma Sintering, microwave sintering, and Hot Isostatic Pressing have changed solid-state sintering capabilities. These methods give faster processing times, better energy efficiency, and superior material properties. On top of that, microstructural control strategies with dopants, second-phase particles, and careful grain growth management help create custom material properties for challenging applications.

Metal Injection Molding stands out as one of the most successful commercial applications of solid-state sintering principles. This method produces complex components with excellent mechanical properties. JH MIM’s nearly 20 years of experience shows how important solid-state sintering is to deliver precision-engineered products globally.

The science of solid-state sintering continues to grow as researchers find new ways to improve densification efficiency while keeping desirable microstructural features. This ongoing development will give powder metallurgy a vital role in manufacturing, with unique advantages in material properties and design freedom compared to traditional production methods.

Key Takeaways

Solid state sintering transforms powder particles into dense components through controlled heating below melting point, driven by surface energy reduction and atomic diffusion mechanisms.

• Temperature control is critical: Sintering occurs at 70-90% of melting temperature, with smaller particles achieving 10⁶-10⁸ times faster densification than larger ones • Three distinct stages drive densification: Initial neck formation, intermediate pore shrinkage, and final pore isolation each require specific process optimization • Multiple transport mechanisms work simultaneously: Grain boundary diffusion densifies while surface diffusion causes coarsening, requiring careful balance for optimal results • Advanced techniques dramatically improve efficiency: Spark Plasma Sintering achieves full density in 5-10 minutes versus hours with conventional methods • Process parameters must be precisely controlled: Atmosphere composition, heating rate, and compaction pressure directly determine final density and microstructure quality

Understanding these mechanisms enables manufacturers to optimize powder metallurgy processes, achieving superior material properties while maintaining dimensional precision in complex geometries like those produced through Metal Injection Molding.

FAQs

Q1. What is solid state sintering and how does it differ from liquid phase sintering? Solid state sintering is a thermal process that bonds powder particles together below their melting point. Unlike liquid phase sintering, it occurs entirely in the solid state without any liquid formation. Solid state sintering typically operates at 70-90% of the melting temperature, while liquid phase sintering requires higher temperatures to achieve partial melting.

Q2. What are the main stages of the solid state sintering process? The solid state sintering process consists of three main stages: 1) Initial stage – neck formation between particles, 2) Intermediate stage – pore channel shrinkage and grain rearrangement, and 3) Final stage – pore isolation and grain growth. Each stage involves distinct microstructural changes that affect the final properties of the sintered component.

Q3. How does particle size affect the sintering process? Particle size significantly influences sintering behavior. Smaller particles generate stronger driving forces for densification due to their larger surface areas. This allows materials with smaller particles to reduce pores more efficiently and form denser structures. According to Herring’s scaling law, 10 nm particles can reach equivalent density levels 10⁶-10⁸ times faster than 1 μm particles under identical conditions.

Q4. What are some advanced solid state sintering techniques? Advanced solid state sintering techniques include Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS), microwave sintering, and Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP). SPS uses pulsed direct current and pressure for rapid densification. Microwave sintering offers energy-efficient volumetric heating. HIP applies uniform high pressure to eliminate porosity and enhance mechanical properties.

Q5. How is solid state sintering applied in Metal Injection Molding (MIM)? In Metal Injection Molding, solid state sintering is the final critical step that transforms fragile “brown parts” into robust, high-density components. The process involves controlled heating just below the metal’s melting point to eliminate remaining binder, reduce surface oxygen, and develop strong interparticle bonds. This enables the creation of complex geometries with excellent mechanical properties.